Within the span of just two weeks in early March, California Community Colleges, along with the rest of American higher education, were forced into the perhaps the largest and most radical pedagogical shift in its history.

Teachers with decades in the classroom who may have only used a computer for little more than email were directed or forced in short order to teach classes which fall into a kind of quasi-netherworld between face-to-face instruction and formal online instruction. The product created as a result of COVID-19 and the need for social distancing is what is commonly referred to as “remote” teaching. It has created unique challenges and concerns for part-timers on the educational front lines.

• • •

On the ground level, the challenges have been considerable, particularly for part-time faculty teaching lab courses. “It’s basically a nightmare,” comments Nikka Osborne-Portillo, who teaches biology at Pierce College and College of the Canyons. In particular, Osborne-Portillo has been faced with the task of teaching dissection online. She says that in each of her classes, she has 2-3 students who in more than two weeks have yet to log into the course shell, and have not responded to her emails.

In terms of curriculum, for her class at Pierce College in the Los Angeles district, Osborne-Portillo has had the benefit of being able to use the recorded experiments of a full-time colleague to provide her students with the visual aid support they need to complete lab task sheets.

At College of the Canyons in Santa Clarita, she has had no such support and is trying to provide support through an amalgam of video clips, self-created Powerpoint presentations, and videos recorded on Zoom so that her students can learn asynchronously. All of this work is in addition to what she would normally do for her courses. She estimates she puts in four times the amount of work she normally does. “It’s depressing, and makes me want to quit.”

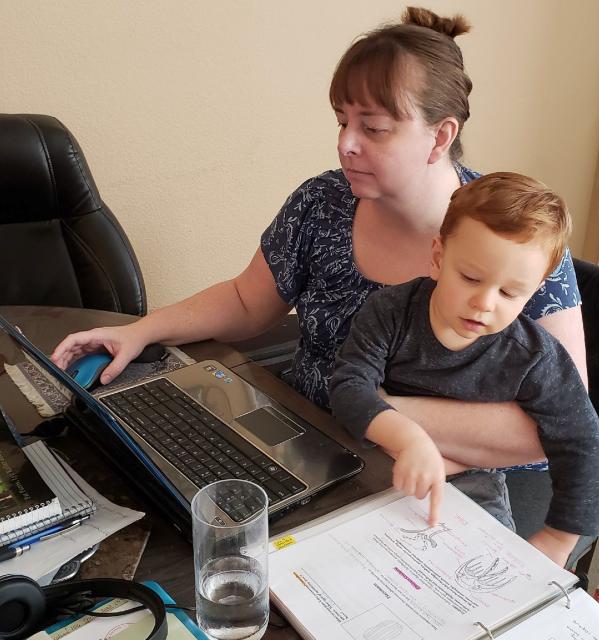

Osborne-Portillo, and her husband Dan, who is an adjunct instructor of English at College of the Canyons, also have to share their teaching time and space with their five-year-old son.

• • •

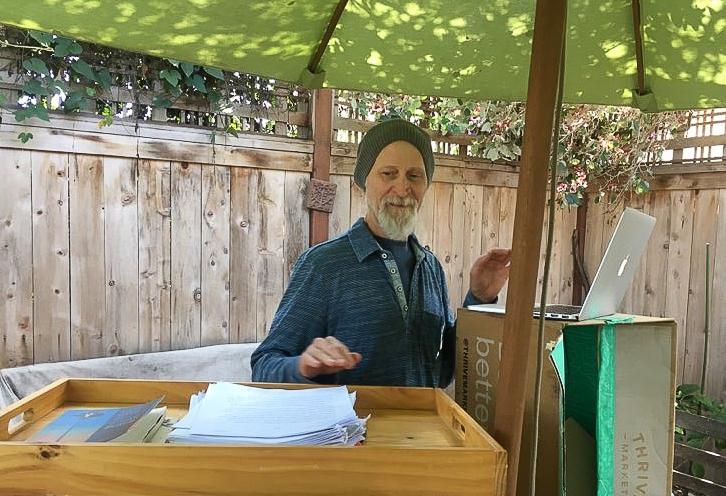

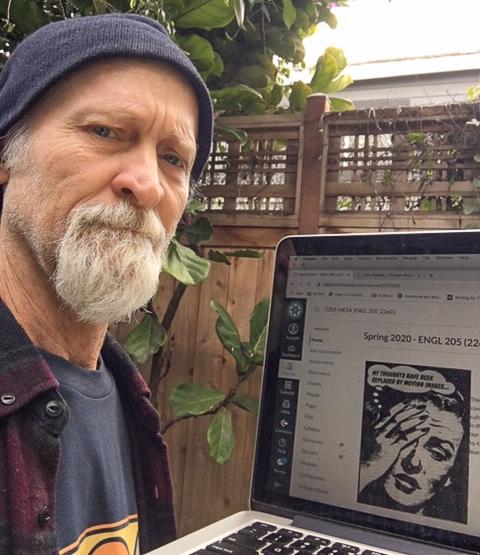

For John Hoskins, who teaches English and Humanities at San Diego Mesa College, his ability to work with students has been complicated not just by converting his face-to-face content to a remote format, but environmental factors, and concerns over the struggles of his students. Hoskin’s wife, Jennifer is a K-12 teacher and both are having to use their laptops at the same time, creating bandwidth problems.

Hoskins, who lives in a small home, also has to deal with a very active dog who frequently barks, forcing him to conduct Zoom sessions with his students on the back patio.

Like Osborne-Portillo, Hoskins is profoundly concerned for the students they have lost with the transition to remote teaching. Hoskins has students who have yet to log-in to the course, and an older student who told him he didn’t want to take the course in a remote format, and subsequently withdrew from the course.

Hoskins has also found that the assignments and quizzes that he gave in his face-to-face course are problematic. “I gave them a multiple-choice quiz in Mythology that I normally give in the course, and they just did terribly.” Hoskins implied that content that was normally picked up by students in the face-to-face class was somehow not getting through. He’s looking to taking a more essay-based quiz format, which will add more work for both him and his students.

• • •

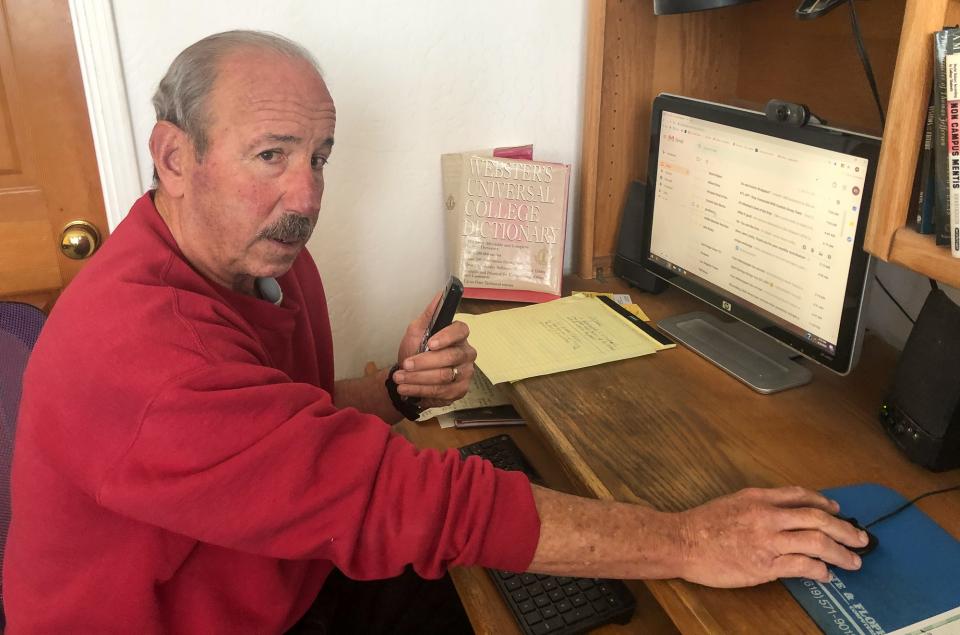

Sadly, many senior part-time faculty are simply overwhelmed by the transition to remote teaching, and opted to let other part-time faculty take over their classes. Mark Linsky, who teaches Political Science at San Diego City College is not one of those teachers. He has stayed the course though the transition to remote teaching has been an especially uphill climb after years of teaching face-to-face.

Somewhat jokingly describing himself as a “bit of a Luddite,” Linsky has been using a combination of Zoom lectures coupled with extensive email communication. He estimates he’s doing double the work he normally does just setting up the class.

Notably though, Linsky’s bigger concerns are with his students. Though he encourages class participation on Zoom meetings, he finds that some 30-40 students in a given section don’t participate. He’s also hearing from his students “heartbreaking stories” of students struggling to support their families as their parents have lost work.

These three part-time faculty are rising to the occasion, but the situation for both them and their students is makeshift, and not sustainable without greater support for both.

— By Geoff Johnson, AFT Guild, San Diego and Grossmont-Cuyamaca Community Colleges, Local 1931, and assigning editor for the Part-Timer newsletter