This is Heather Molloy’s first year on CFT’s Special Education Services Committee. She says she feels grateful to be part of it and thinks in a short period of time, the committee has accomplished a lot.

Molloy, a high school teacher and member of Oxnard Federation of Teachers and School Employees, is referring to the EC/TK-12 Council’s Special Education Summit in February where members wrote a resolution to change the state’s Education Code, which she thinks desperately needs updating.

“The current Ed Code is really outdated and very nonspecific,” she said. “It leads to districts creatively solving problems and hurting the workers in the long run.”

What kind of creative solutions hurt workers? Well, giving teachers more work without more support. Special education teachers have lots of additional paperwork with student Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) that need to be scheduled and managed and written.

The resolution reads in part, after mentioning that the number of teachers without full credentials has increased “…oftentimes resulting in fully credentialed special educators picking up the work of developing IEPs for students who are not on their caseloads and making them responsible for a disproportionate amount of IEPs relative to their own caseloads.”

That’s what’s happening at her school, Molloy says. Under the current Education Code, her caseload is 28, but there’s nothing specific about how many IEPs she has to do, and that results in students she’s done IEPs for being taken off her caseload and her getting more. She adds that IEPs have gone from eight pages when she started teaching 10 years ago to around 17 pages.

“On any given year, I will probably hold 34 or 36 IEPs,” she said. “One year I had 57 because I worked for a district that allowed it to happen. It happens all over the state and it’s an abuse of power.”

They need specific numbers for how many students a teacher can have based on the programs, so kids are better served, and teachers have some sort of protection, Molloy says.

“We looked at other states’ Ed Codes, and they do have those types of things written in,” she said. “We’re just asking for same consideration.”

For districts who say it’s too difficult to hire more special education teachers, Molloy, the author of School’s Out: A Daily Countdown and Guided Journal for Educators, wants some creative solutions. She says she knows teachers who have left because instead of spending their time teaching, they were bogged down in paperwork. She’d like to see ways to relieve that burden on teachers, including those at the district level with special education background helping with IEPs.

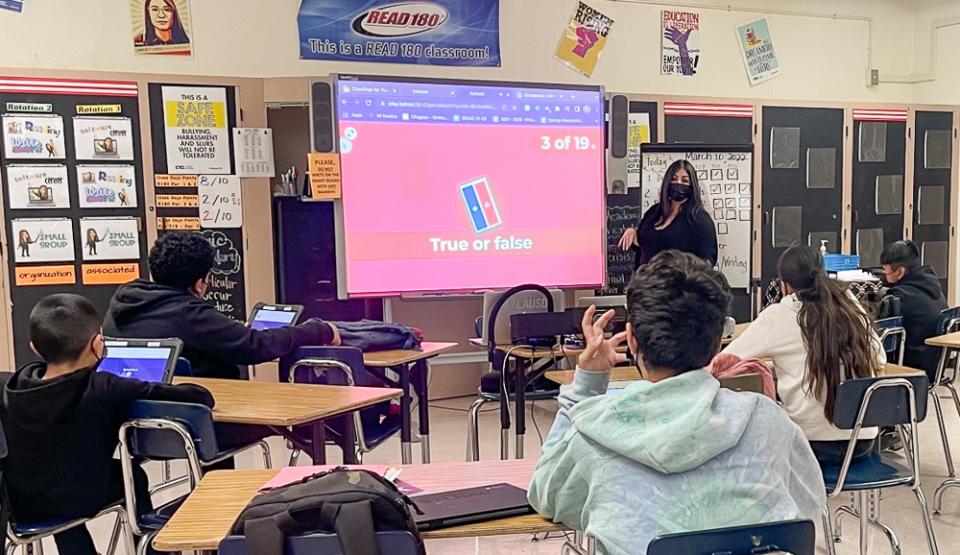

Marcela Chagoya, the chair of the CFT Special Education Services Committee, agrees something needs to be done to help teachers out and to keep them in the profession. Chagoya, a teacher at L.A’s Stevenson Middle School, has been teaching for 21 years. Everyone else in her department has been there less than five years.

Chagoya, a member of United Teachers Los Angeles, says when she really started looking into special education programs around the state for her role as committee chair, she was shocked by the lack of uniformity on every level from salaries to services to programs.

One example of that is resource specialist teachers, Chagoya said. Since there is no language in the Education Code about their duties, in some districts, including hers, they go into the general education classes and help, but in others, they have their own classes.

“There’s quite a burn out rate with all the different hats they have to wear with writing IEPs and testing students and teaching,” she said. “Your caseload is supposed to be 28, but it’s not 28. If we get new students, the initial IEPs are not counted, and you could do 30 or 40.”

The resolution calls for limits on how many students are in a class, which will benefit the students, Chagoya says. She just helped file a grievance about a class in her district where there are 14 children with autism, for example.

Chagoya says the next step is for the executive council to pass the resolution, then to find a legislator to adopt it, and after that to create a campaign that involves teachers, parents, students.

Parents of students in special education tend to be strong advocates, Chagoya says. She entered the profession because her brother has autism, so she knows firsthand.

“We advocate and we’re loud and we’re persistent,” she said. “Special ed is a hot topic now. Our own president had a disability — he had a speech impediment, and his wife is a teacher.”

The pandemic highlighted the problems in a not well supported system, says Rico Tamayo, president the EC/TK-12 Council. He says one example is getting a substitute — or not getting one.

“It was not easy to get a sub before and it’s virtually impossible now,” he said. “One special ed teacher I know can pretty much never take a day off even if she were to get sick. There is simply no one else to teach the class.”

These are also concerns for general education, Tamayo says, and he hopes focusing on these issues as well as teacher recruitment and retention will help everyone. He left the summit envisioning a big campaign that could include parents, teachers, community members, and administrators, all focused on getting students the services and support they need.

“If we lobbied together as a team, it would be historic. We all want the same thing,” he said. “I got excited at the summit, and that doesn’t often happen. I get so cynical — we shake our fists and make some noise, and sometimes there are little, incremental changes, but I’m telling you at this summit it’s been a while since I felt that galvanized, like we’re not going to take it anymore.”

— By Emily Wilson, CFT Reporter