Ways to honor Black History Month at school and home

February is Black History Month

On February 1, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln approved a joint resolution to submit the proposed 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery, to the state legislatures. While the history of Black Americans involves so much more than slavery, it is imperative that students fully understand the institution of slavery, its dissolution and the aftermath in order to understand today’s racial inequity.

We have compiled some meaningful collections of resources for Black History Month. These resources may be of interest to educators in the classroom, unions, and families and communities.

Celebrate Hispanic Heritage Month at school and home

Honoring Latinx history and achievement September 15 to October 15

Hispanic Heritage Month takes place September 15 to October 15 every year to recognize and celebrate the contributions, diverse cultures, and histories of the American Latino community. With California’s Latino population continuing to grow, and to make up nearly 40% of the state, it’s particularly important to recognize accomplishments and history. In fact, two of the state’s most iconic labor leaders, Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, the founders of the United Farm Workers, are Latino.

Celebrate AAPI Heritage Month at school and home

May is Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month

The month of May was chosen to commemorate the arrival of the first Japanese immigrants to the United States on May 7, 1843, during the beginning of the California Gold Rush. It also marks the anniversary of the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad on May 10, 1869. Most of the workers who laid the tracks that connected the frontier to the rest of the country were Chinese immigrants.

Dismantling male supremacy and white supremacy

Workshop takes a deep dive into building healthy workplace cultures

Bill Pritchett, a specialist in racial justice, communications, and leadership development, and who guided CFT’s Racial Equity Task Force, began his workshop on “Dismantling the Intersections of Male Supremacy Culture and White Supremacy Culture in Our Workplaces” (whew, tall order) by talking about how impressed he is with CFT’s commitment to racial justice.

Members support and mentor undocumented students

Dedicated educators help students succeed and thrive

For Belinda Lum, sociology professor at Sacramento City College and chief negotiator for the Los Rios College Federation of Teachers, it was because she’s the granddaughter and great-granddaughter of people who came over from China with fake papers. For Leis Rodriguez, it was wanting to use her law school degree for her passion and becoming an immigration attorney.

How implicit bias can lead to injustice

Members explore implicit bias and its effects

Implicit bias can lead to injustice in many areas of our lives, including housing, education, employment, the courts, and healthcare. We all have implicit biases — or preferences and attitudes that subconsciously can affect how we interact with others, said Bethany Gizzi, and Lena Ackerman, trainers in the “Understanding Implicit Bias and Stereotypes” workshop at the CFT Leadership Conference held March 17-18.

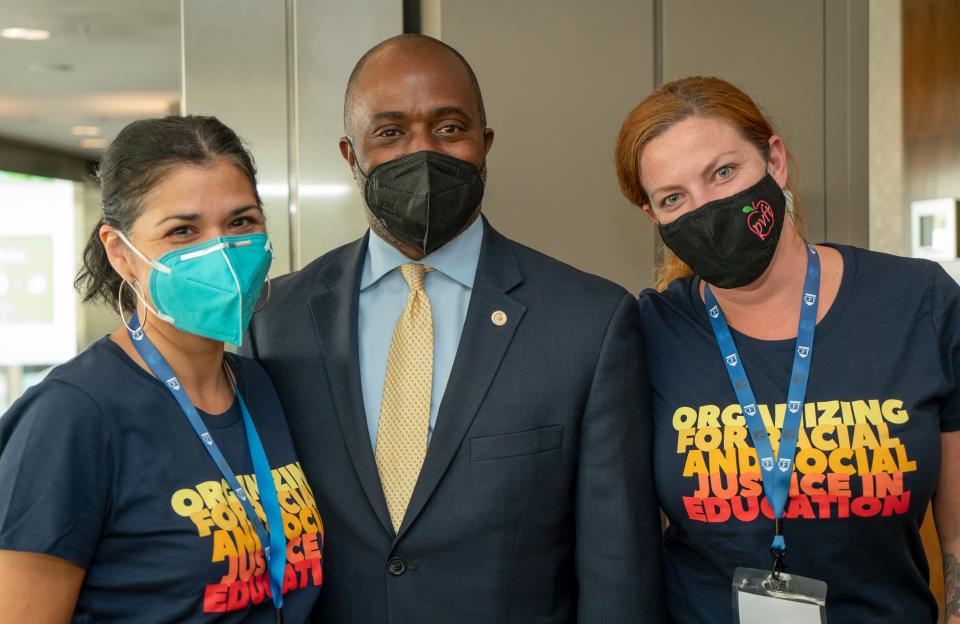

Leadership Conference focuses on racial and social justice

Thurmond, Weingarten address delegates

About 200 CFT members from around the state converged at San Francisco’s Hyatt Regency for a Leadership Conference — the first time they’d been able to join together for such an event since the state shut down for COVID on March 13, 2020.

Seeming excited to see one another in person, attendees went to workshops, many dealing with racial and social justice issues, and heard from speakers including JEDI (Justice, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion) Organizer Cynthia Eaton, State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond, and AFT President Randi Weingarten.

Stand up to defend free thought, honest history, and gender identity

Right-wing targets schools and colleges across the nation

By Jeffery M. Freitas, CFT President

When I decided to become a teacher, I was focused on helping students and meeting them where they are. I became a mathematics teacher — slopes, quadratic equations, fractions, square roots and all. But I entered into the profession because I was interested in who my students are as people, not just in class. I wanted to understand their hopes and dreams and help them become the people they wanted to be.

Khalil Gibran Muhammad on racial justice

“Good will is not a substitute for good work”

A history professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School, who teaches classes such as Race, Inequality, and American Democracy and the former Director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, with his work featured in the New York Times’ 1619 Project, and Ava DuVernay’s documentary about mass incarceration, 13th, Khalil Gibran Muhammad s

“Let’s have our voices count!” urge CFT Black leaders

Avalanche of protests call for racial justice following murder of George Floyd

For days, hundreds of thousands of people have filled the streets of 160 cities across the country, even during the coronavirus pandemic, expressing their outrage and grief at the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Two Black leaders of the CFT, with long histories of fighting for racial equity, say they could not help being profoundly moved by the murder itself, and the outpouring of rage in response.

Union work is social justice work

By Jeffery M. Freitas, CFT President

When I was elected CFT President in March, I said in my speech to Convention delegates: “I believe that when we fight for education, we also fight for social justice, racial justice, gender equality, LGBTQ rights, and climate justice.”

To be a social justice union, we must not only consider the complex lives of our members and the challenges they face, but look beyond the doors of the schoolhouse to consider the ways our campus communities intersect with our larger communities. When we fight for labor, we must fight for our communities, too.

CFT members testify before Select Committee on Ending the School to Prison Pipeline

On Wednesday, June 26 three CFT members testified at the State Capitol at the first ever hearing of the California Assembly Select Committee on Ending the School to Prison Pipeli

Racial Equity Task Force delivers draft report to CFT Convention

UPDATE: On April 1, delegates to CFT Convention unanimously passed Resolution 14 titled “Reclaim the promise of racial equity for Black males in California,” which called for adoption of the report written by the Racial Equity Task Force.

Were You a Racist?

On the Friday before Martin Luther King, Jr. day, I asked my fifth-graders if they knew why we had the day off. One suggested, “To celebrated MLK’s birthday.”

To be honest, for a ten-year-old that wasn’t bad.

“No,” another piped in, “It’s cuz he fought for blacks’ rights.”

“Good and you’re 100 percent correct.” I replied. Let’s call the child who piped up with that answer Isaiah. He’s perceptive and often sees the big picture.

Classified Conference 2016: Black Lives Matter conversation engages, unites

“When we say Black Lives Matter, we’re saying that we need an agenda that puts our lives right up there with everyone else’s,” said Christopher Wilson, from Alliance San Diego, a group mobilizing for change in low-income communities and communities of color.

Wilson spoke at the Classified Conference on October 8, before attending the funeral for Alfredo Olango, a black man killed by police in nearby El Cajon.

Racial justice: Tim Wise says the purpose of education is to get free

Whenever we see inequalities in our society we need to remember one thing, antiracist activist Tim Wise told attendees — there are no accidents, just precedents.

Wise, who has written seven books, most recently Under the Affluence: Shaming the Poor, Praising the Rich and Sacrificing the Future of America, talked about how the inherent injustice of the educational system must be transformed — the system was never meant to bring equity.

Restorative justice seeks to end the school-to-prison pipeline

How educators can help transform classrooms and school climates

If an African American male student is suspended, there’s a 90 percent chance he’ll end up in prison some time in his life. In 2013-14, there were half a million suspensions in California schools, many those of black and brown children. These statistics make equity in education one of the great civil rights struggles of our time, said Ali Cooper, the executive director of the Restorative Schools Vision Project.

“No Time to Quit”

A look at school desegregation by former CFT President

By Miles Myers, Former CFT President

In the nation’s first school desegregation case, on February 13, 1931, in Lemon Grove, California, the Mexican parents of Roberto Alvarez went to court to stop the Lemon Grove Grammar School from denying access to Mexican children. A victory for Roberto in the local court stopped the case from reaching the U.S. Supreme Court. But the same issue did reach the U.S. Supreme Court almost twenty-two years later (1953) when the Black parents of ten-year-old Linda Brown sued the Topeka (Kansas) School Board, demanding that skin color (and race) not be used to deny her access to her neighborhood public school. Unlike the Lemon Grove court, Topeka courts did rule that skin color could be used to deny Linda’s entrance to the nearby public school and, thus, the case was appealed to the Supreme Court. Her local public school, she said, was her gateway to opportunity, and thus, that gateway should not be blocked by segregationist policies. She won.