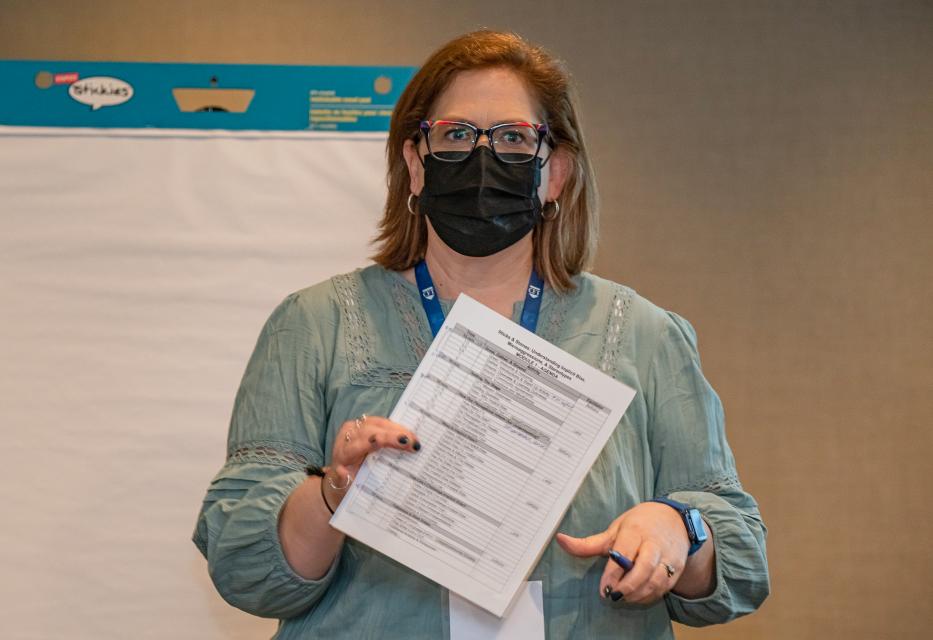

Implicit bias can lead to injustice in many areas of our lives, including housing, education, employment, the courts, and healthcare. We all have implicit biases — or preferences and attitudes that subconsciously can affect how we interact with others, said Bethany Gizzi, and Lena Ackerman, trainers in the “Understanding Implicit Bias and Stereotypes” workshop at the CFT Leadership Conference held March 17-18.

Working on the premise that recognizing these biases is a step towards working for equity and fairness, Gizzi, a sociology professor and president of New York’s Faculty Association at Monroe Community College and Ackerman, assistant general counsel for New York State United Teachers, gave some strategies to understand biases and stop them from influencing our behavior.

Gizzi asked participants to try and stay engaged during the workshop even if they experienced discomfort, and to pay attention to their thoughts and be compassionate. “Expect non-closure,” she said.

After participants discussed ways they’d experienced bias themselves or seen it affect others, they talked about ways to react when people say biased things to you. Ackerman, whose maiden name is Mukherjee, said sometimes when she’s on the phone, people will make statements to her, thinking she is a white woman. One way to react, the trainers said, is to ask the person why they said what they said.

Gizzi and Ackerman had several exercises for the participants to do — looking at a picture to see how many cubes there were, naming the colors when they didn’t match words (the word “blue” in red, for example), saying everything you noticed about a picture, and picking out the number of Fs in a statement (we tend to see the ones at the beginning of words, but miss the ones in ‘of” for example).

Gizzi likened our perceptions of the world to a prescription for glasses, with factors like cultural background, education, home life, and the state we live in influencing the way we see the world.

“We don’t always get the complete picture,” she said. “How we grew up and were socialized feeds into our narrative.”

The trainers also showed videos including “The Look,” where people react in negative ways to a Black man — not holding the elevator for him, a driver rolling up the car windows when her daughter waves at his son, looking at him oddly when he and his son are in the pool, choosing not to sit near him at a diner. At the end of the video, the scene is a courtroom where he’s the judge. Ackerman shared how early in her career when she would come into court, others would assume she was the court recorder rather than a lawyer and point her to an outlet as an example of stereotyping.

Ackerman gave examples of explicit bias such as a landlord saying they wouldn’t rent to certain groups of people, or implicit bias, like only running background checks on Latinos. She also talked about a man sending out the exact same resumé, one with the name Pedro and one, Peter, and getting lots of responses to the latter.

“There are all kinds of studies about that,” she said. “It’s how implicit bias is used, usually in a way that’s harmful.”

Media also influences our perceptions. The trainers presented two photos from stories after Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. One showed a photo of Black men wading through water with some bags and a caption saying they’d looted and a similar image of White men with a caption saying they had found the food they were carrying.

The trainers gave some concrete strategies people could do to recognize their own biases and not act on them. They included taking the implicit association test, slowing down and being more intentional about actions, and thinking about the perspective of other and exploring different interpretations.

— By Emily Wilson, CFT Reporter