Computer geeks have been on the front lines of online learning since March, when school and college districts across urban and rural California closed to avoid the COVID-19 pandemic. Tech staff are the essential employees who are turning digital classrooms from a pipedream into a working educational system.

Palomar Community College’s emergency response team met regularly for years to prepare for disaster, but most scenarios featured earthquakes or wildfires. Coronaviruses weren’t a likely threat.

“We weren’t set for this,” said information services tech George Frederick, “but we’re doing very well with what we have. Palomar was good about ramping up when this crisis began growing.”

Palomar techs are divided into two departments. Nearly 30 Information Services staff handle security and passwords, the help desk, and the campus switchboard. Frederick normally works the help desk.

Meanwhile, about a dozen Academic Technology staff support websites and coursework, such as setting up Canvas accounts for faculty. Canvas accounts are like online forums; each instructor gets one and students are invited to attend.

Together, these classified employees support Palomar’s main San Marcos campus and seven satellites across northern San Diego County.

Most Palomar personnel moved off campus quickly, but Info Services retreated gradually. Techs linked “remote desktops” to their office computers to access programs and other secure data that can’t be loaded on outside networks.

Before the crisis, the help desk would receive up to 600 calls daily. The desk received about 1,200 calls the day after the campus exodus.

“What we accomplished in two to three weeks was astonishing,” Frederick said. “That’s a tribute to the entire campus, not just the emergency response team.”

Information Services spent spring break bracing the network for the major challenge of distance learning through the fall.

Frederick is a member of Palomar’s Council of Classified Employees and sits on the AFT Local 4522 negotiating team. “We’re all very lucky to still be employed, and we’re still employed because of the unions.”

• • •

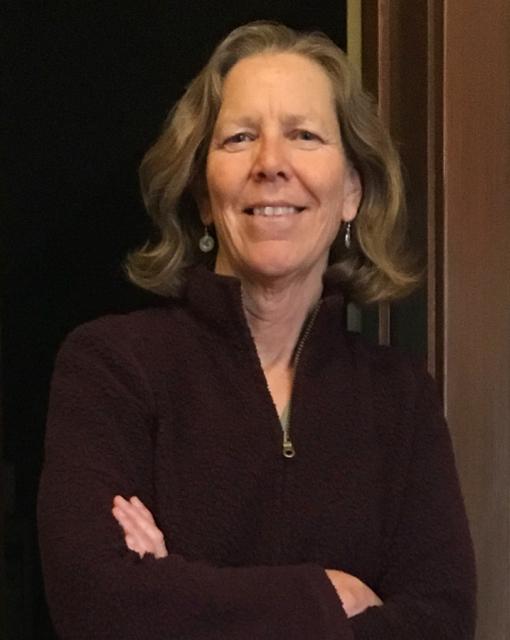

Anne Robert has worked in tech for 20 years, including more than 10 years with the Berkeley Unified School District. Robert and six other techs serve three preschools, 11 elementary schools, three middle schools, one high school, and one continuation school.

Robert was based at Longfellow Middle School, but the only employees still on campus are food service crews distributing “grab and go” meals to students and families.

The techs replace hardware, fix software glitches, determine after-school needs, and make recommendations for which new technologies to adopt. They now perform most of that at home. Tasks range from the complex to the mundane, but Robert describes her bigger mission as “making sure teachers and students have the tools they need for distance learning.”

Berkeley schools used Zoom for two days, until hackers “bombed” the videoconferences. The district switched to Google Meet because it can authenticate online addresses. Student accounts with berkeley.net have content filters to keep them safe.

Robert, a member of the Berkeley Council of Classified Employees, AFT Local 6192, has a son in seventh grade, and stays in touch with his teachers.

“Teachers really miss their students and want to stay involved,” she said. “They are allowing families a lot of leeway, given the emotional and other problems people are facing. At the same time, they are doing what they can to keep kids involved and learning.”

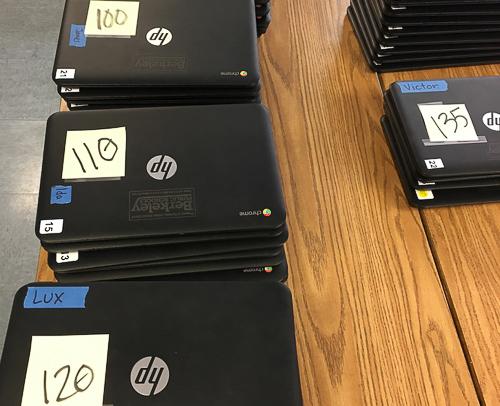

Robert recently returned briefly to Longfellow to take possession of and prep 600 Chromebooks, which were assigned to families and distributed in a drive-through line.

Google Chromebooks have shot to the top of a crowded digital market. Samsung, Hewitt Packard, Acer, Toshiba and Dell all offer sturdy tablets for about $250, well under the iconic Apple iPad.

Robert and other techs attribute the Chromebook’s popularity to low price, functionality and features like Google Meet, Google Education, Google Docs, and Google Classroom.

Statewide, private tech companies have stepped up to donate 70,000 computers, tablets or other devices. Apple has distributed 10,000 iPads to 800 school districts. Google has given out 4,000 Chromebooks and started to create the first of 100,000 pledged hotspots in early May.

• • •

Normally, about 20,000 students fill the sprawling Pierce College campus in suburban San Fernando Valley. It is one of nine schools in the Los Angeles Community College District, the state’s largest community college district.

Pierce’s tech support department, with up to 18 staff members, is the second largest in the district. The campus is quiet now, but the techs are working harder than ever by remote connection.

Suleman Ishaque works mainly with students and counselors. A large part of his job is adapting digital devices for Pierce’s estimated 1,400 students with vision and hearing problems and other disabilities.

Before the crisis, some Pierce instructors were teaching online, but no classified employees were telecommuting. Ishaque was able to perform most of his work remotely, and has since been given greater access to the campus network.

During the exodus, Ishaque prepped and distributed Chromebooks to students for distance learning, and to faculty and staff who would be working from home.

Ishaque is second vice president of AFT Local 1521A, the College Staff Guild, and he blasted the district’s inequitable treatment of staff at the start of the crisis.

“Faculty and student workers were sent home with pay, but classified were told to report, even though we didn’t have appropriate PPE,” he said. “I don’t know what administrators were thinking when they came up with that policy. A life is a life.”

Ishaque, who also sits on the CFT Educational Technology Committee, described working from home as bittersweet. “I miss the union and workplace activity.”

There were hiccups and stumbling blocks, he said, but the dust is settling. “We’re doing better, but who knows what the overall effect of all these changes will be for students in the long run.”

• • •

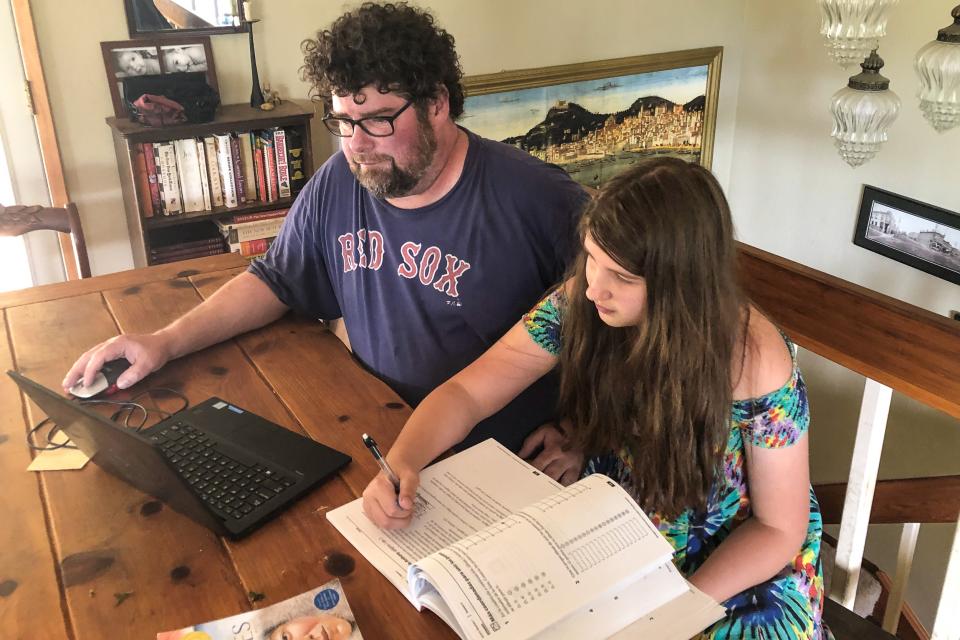

Emory Upchurch has lived in Ukiah for 18 years, and worked in technical support for the Mendocino County Office of Education for 10 years. Upchurch and four other techs serve 13 school districts across the large Northern California county.

The tech team had two days to shut the county office and begin working from their homes. They now check in every morning by Zoom.

Mendocino’s largest school districts are Willits, Fort Bragg and Ukiah, the county seat where the county office of education is based. Smaller districts have as few as 100 students and not a single tech on staff.

Before, Upchurch said, he might visit the town of Covelo in the county’s remote northeast corner three or four times a year. Now he solves problems by phone whenever possible. His new watchwords are “shelter in place.”

Upchurch occasionally visits the closed county office to grab a replacement for someone’s broken laptop or fix a teacher’s device in the parking lot. Most of the time, though, he’s solving problems from home while his fourth grade daughter and ninth grade son do their schoolwork.

Mendocino County schools had a head start on distance learning. Many students were already in online education programs, and digital tablets were widely deployed in middle and high schools.

The county, however, was hard-pressed economically and losing population even before the national shutdown.

“Except for vineyards and farm work,” Upchurch said, “there’s not a lot of jobs. When the timber industry collapsed, a lot of people didn’t have the skills to take part in the technology-driven economy.”

Many staff and students can’t afford high-speed internet connections, he added. “A kid can’t do a daily Zoom chat with his teacher on a dial-up modem.”

One in five California children – about 1.2 million students – do not have an internet connection or a digital device to access remote learning. Gov. Gavin Newsom announced that the state will spend $30 million to connect more households, including $25 million from the California Teleconnect Fund to be earmarked for rural, small and medium-sized districts.

Upchurch hopes the Mendocino County Office of Education will follow the lead of Sacramento, where transit officials have converted school buses into wi-fi hotspots. They park the buses in school lots so families can drive in and park near the bus so their children can hook up to the internet and join their teachers and classmates online.

— By Steve Weingarten, CFT Reporter