In a history-making move, the University Council-AFT is taking steps to expand representation in its leadership. Two new vice presidents have been elected, both of whom are contingent faculty from campuses that have not previously been represented — UC Merced and UC Irvine. Iris Ruiz, from Merced, is the first woman of color to serve on the UC-AFT Executive Board. Trevor Griffey is the first labor historian; he also has a pre-continuing and intermittent appointment.

“I’m happy to have activists stepping up from across the state,” said Mia McIver, UC-AFT president.

Iris Ruiz teaches first year composition, journal editing, Chicano Studies, and upper division academic writing at UC Merced. As the new Vice President for Grievances, she says being the first woman of color gives her an advantage. “I can see cases that show a pattern of discrimination, for instance, because I’ve experienced that myself. That can include discrimination in dismissals, hiring, and how positions are assigned. Some of that is blatant and some is subtle.”

Ruiz has been teaching for 20 years, starting at UC San Diego where she got her doctorate. There she taught legal writing as well, which gives her additional insight into the way union contract language is written and can be enforced. Teaching Chicano Studies has given her insights as well. “I’ve always been interested in power relationships — class, gender and racial — between groups and society as a whole. Seeing it through an historical lens has helped me learn more about who I am, and as a Democrat it has made me aware of inequality.”

She questions, for instance, why the university system is so determined to uphold the inequality between ladder and non-tenured faculty, and sees the new UC-AFT contract as a big achievement. In it the union broke through on one of the most important issues for the last 50 years — the precarious nature of lecturer jobs — by winning a process of reviews and preference for classes that lead eventually to permanent appointments. “It’s not 100%, but it’s a big step,” she emphasizes.

As one of her first actions, Ruiz has participated in drafting a petition that charges that the university is now trying to circumvent the contract’s protections by creating teaching positions it claims are outside of the bargaining unit, and then excluding people in those positions from the contract’s rehiring rights. “This will also take courses away from our own members, and it’s a danger to the union,” she warns.

Using a petition — collective action — in addition to the formal grievance process in the contract is an idea with social movement roots. “As a Chicana, I can’t separate myself from history, and I see the gains of my people won through the grape boycott and the Delano strike, led by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta. They’ve influenced my own ideas about how organizing takes place, from the bottom, and have something to teach our own union.” She views grievances as organizing opportunities, and works closely with Josh Brahinsky, Vice President for Organizing.

It’s good, she says, to be the first woman of color to be a UC-AFT vice president. “It’s a great responsibility, and I feel honored and proud. But I also have to ask, why, in 2022, am I the first one?”

• • • • •

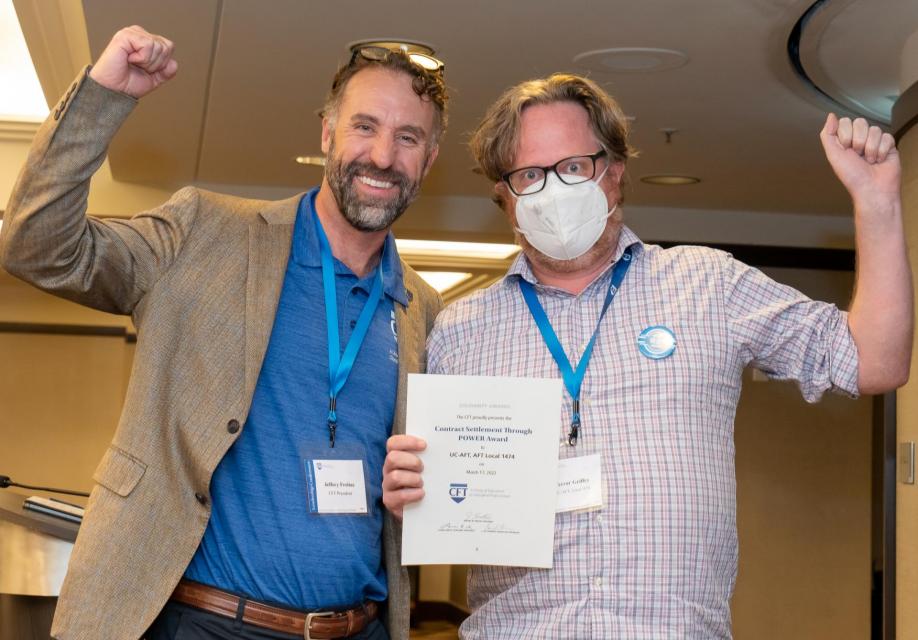

Trevor Griffey also comes from a background of activism in civil rights. His main appointment is at UC Irvine, where he teaches labor history, a research seminar that currently looks at the Black freedom movement’s relationship with the FBI, and a third course on U.S. politics. He also teaches at the UCLA Labor Center, a course looking at labor in the public education system. He’s written for professional publications, like the Labor and Working Class History Association, and spoken at their conferences. “Trevor has a pre-continuing and intermittent appointment, so it’s notable that he’s serving in leadership while being part-time and very precarious,” McIver says.

Griffey’s labor activism was forged in his experience before getting his doctorate. He went to the University of Washington the year after the strike by graduate students successfully won union recognition. “I learned that the reason why we had health benefits and raises was because we had a union.” His PhD project was supported by the Harry Bridges Institute, which was founded with the contributions of retired union members, especially longshore workers.

Then, however, he experienced the predictable exploitation that came with being an instructor in the state university system, first in Long Beach and then at Dominguez Hills. “It was a sausage factory,” he says, “where departments had more adjuncts than tenured faculty. And as adjuncts we taught classes of 50 students, 200 to 300 students each semester. Tenured faculty had half the students and three times the pay. I felt we were teachers destroying our own profession from within.”

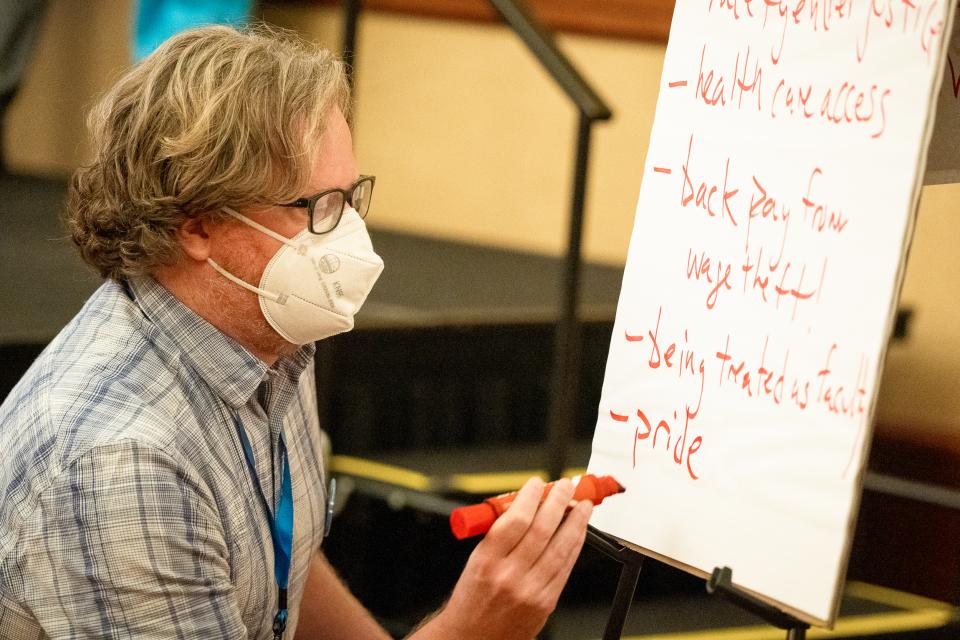

At the state universities his response was to become an activist, trying to get the union there to mount a militant defense of its members. Griffey brought that attitude with him when he made the change to the UC system. He got involved in the three-year campaign to win the 2021 contract. “My background was organizing, walking the hallways, talking to people, asking them to join the union and the campaign,” he explains. I saw that in bargaining we were led by our own union members, even holding children in their laps as they confronted the university’s highly paid lawyers. And because of all that, we got what we needed to win.”

Once the contract had been won, Griffey and other campaigners breathed a sigh of relief. “That campaign developed a lot of leaders, and an intense organizing attitude, being ready to strike,” he remembers. “But then we asked ourselves what was next for the union. I thought that running for Vice President for Legislation would be a chance to push for even broader goals, especially the restructuring of higher education. In other parts of the system, like the community colleges, people are even more exploited and we should support them. At the same time, we need to reform the UC system itself.”

Griffey is now active in Higher Ed Labor United, a coalition of unions and organizations representing hundreds of thousands of education workers. “If we combine legislative advocacy with organizing, and labor struggle with student organizing, we can have power even the tenure track faculty don’t have,” he predicts.

— By David Bacon, CFT Reporter