As hundreds of lecturers, students and other workers at the Berkeley campus of the University of California gathered in front of the MLK Student Center, they began to chant. “UC would not be anything, Without teaching faculty, ME!” Leading them was Lacy Barnes, senior vice president of the CFT, and former full-time faculty member and president of the State Center Federation of Teachers.

“Every day,” she told the crowd, “UC teaching faculty are transformatively engaging their students on multiple levels academically, social, emotionally and civically. Every day across this state, UC teaching faculty change lives.” Yet, she charged, UC administrators deny them respect. The UC system prefers to treat these hardworking lecturers as throwaway academic gig workers. That lack of attention stops here today! Education is not a business and lecturers aren’t the bargain big parts that the UC can use to save a buck, but that’s how they are being treated.”

At rallies on every UC campus, like the one at Berkeley, lecturers spoke out this week against churn — the practice in which the university encourages a high rate of turnover. Stopping the churn is one of the key demands that the lecturer’s union, the University Council-AFT, has prioritized in a two-year struggle to get UC to sign a fair contract. The old agreement between the union and university expired on January 31, 2020, and negotiations have dragged on ever since.

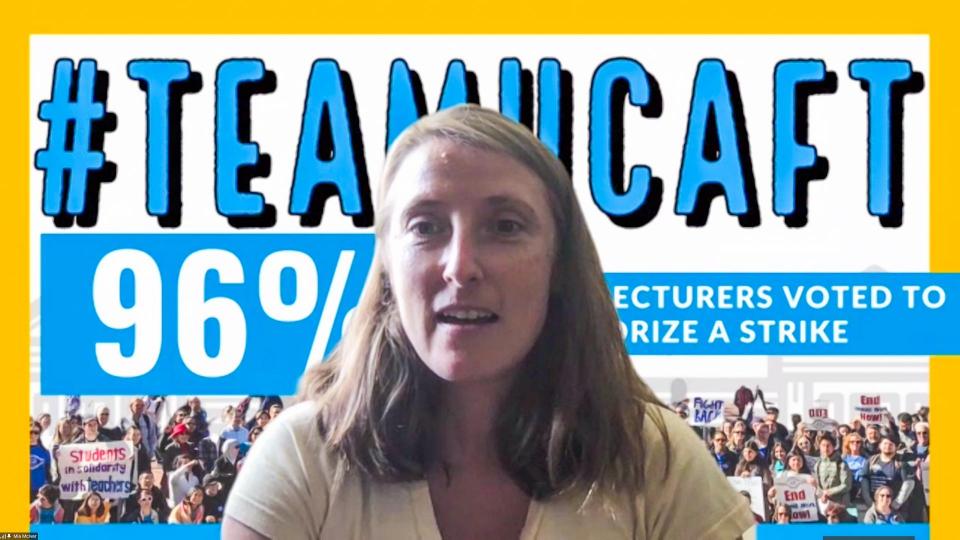

The rallies over two consecutive days sought to give the university a message — that the union is prepared to strike if necessary, and has the support among other UC workers and students to make such action effective. In April the union took a strike vote, and a majority of lecturers cast ballots, approving that action by 96%.

Job security is the most important issue. After strikes on some campuses in 2002 and a three-year campaign, the union won continuing three-year appointments for lecturers who complete six years of teaching and pass an exam called “passing through the eye of the needle.” The university has to renew the appointments so long as classes are available the lecturer can teach.

Only 7.8% of lecturers since 2003 have had continuing appointments. Lecturers at the rally explained it is difficult for lecturers to reach continuing status, because the closer they get to the six-year goal, the likelier it is they won’t be rehired.

Forty percent of the contracts for lecturers with less than six years are not renewed for the next year. “We teach a third of all the credit hours on campus,” said UC-AFT President Mia McIver in an interview following the strike vote. “But over half of lecturers teach one year or less, and the average length of service is less than two years. UC negotiators continually hide behind management rights, and say they shouldn’t have to give a reason for not rehiring someone. What they really want is contingent employment with no evaluations and no due process.”

UC-AFT has proposed better protections for the job rights of lecturers as they continue teaching, especially their right to be rehired from one year to the next. In addition, the union proposes pay increases, since the low median salary for lecturers, $19,067, is another factor in producing the churn. The number of courses a lecturer with a continuing appointment can teach is three per semester at Berkeley — eight per year if a lecturer teaches two semesters and two courses over the summer. That produces a yearly income of $57,000, according to a recent report by CalMatters — not enough to live in Berkeley or West Los Angeles, where UC’s two biggest campuses are located.

That report confirmed the analysis in two articles in CFT United, published this past year. Lecturer turnover, it noted, “has been an average of about 1,440 lecturers annually and peaked at 1,618 in 2020.” Yet the university depends on the lecturer workforce to teach over a third of all classes to the system’s 285,000 students.

Many signs and chants at the Berkeley rally condemned a further indignity, in truth robbery, to which lecturers are subjected. The university will not pay for much of the work they do, such as counseling students and writing letters of recommendation. This became a more critical issue during the pandemic, when lecturers had to teach their courses online, going through training, mastering the necessary software, and offering additional help to students. The university provided no extra pay for any of this work, as other institutions have done. This became the subject of an unfair labor practice charge by the union.

In bargaining, all the four most fundamental issues remain on the table — high turnover rates, lack of performance reviews, widespread uncompensated labor, and compensation itself. The union has declared that negotiations have reached impasse, and a mediator is meeting with both union and administration negotiators.

The long line of speakers at the Berkeley rallies was evidence of the support lecturers will have if they strike. They included leaders of AFSCME, UPTE-CWA, UAW and other university unions, and student and community activists. At the end of the second Berkeley rally, the crowd marched to University Hall behind the banners of the union and Young Democratic Socialists of America.

David Walter, a lecturer who chaired the rally, shouted out as the marchers began their procession, “This is just a small piece of the hell the university can expect if things don’t change radically, and quickly.”

— By David Bacon, CFT Reporter