Q: Tell me, how long have you been working here?

A: Ever since they threatened to fire me.

That old cornball joke still makes me laugh, 50 years after I read it in a kids magazine. I understood it then as honest if everyday acknowledgement by the presumably once-lazy worker of his or her required acquiescence to power, and of isolation. But its splendid trick syntax and on-the-nose calling out of the coercive relationship of management to labor suggested more, even to a 10-year-old: cognizance of at least the potential inherent power of the worker — all workers? — to apprehend, to subvert, to jest, however fatalistically, cynically or — my own favorite — insubordinately.

I’ve frequently shared this vaudevillian humor cum agitprop with fellow part-time teaching colleagues and union comrades. We are called “lecturers” at the big public university where I work. Those who’ve taught for more than even a single quarter as “adjunct,” “part-time,” “contingent” (you choose) labor immediately apprehend its gentle evocation of our shared precarity and embarrassing second-class status among faculty, despite (or because of) teaching more than half of the undergrad offerings in the University of California system. So, yes, they get it.

But telling this smart dumb joke has also helped explain our working conditions to non-teachers, students, parents and the otherwise curious types who wonder — often only casually, fleetingly, or when forced to — about what it’s like to be Non-Senate Faculty, untenured, “freeway flyers,” in fact the increasing majority of higher education instructional employees. We don’t get much attention, or justice, yet there sure are a lot of terms describing us, a rose by any other name still as thorny.

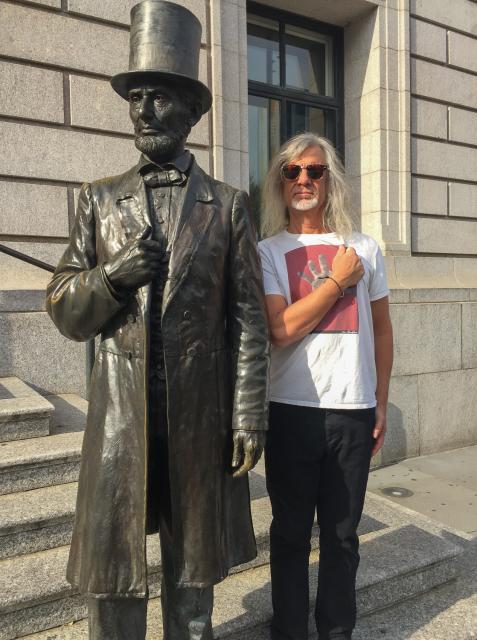

Of course, readers have by now recognized my multi-purpose joke-telling as a gesture of purposeful provocation, and also recognized a provocateur. I am a long-time smart-ass writing teacher activist with vigorous left politics and, still, somehow, a sense of humor — a requirement of the job, especially after 20 years of reading freshman composition essays, a job which tenured faculty do not do, and for a reason. Meanwhile, I insist on teaching, modeling, and immersing students in civic literacy and politics (including labor justice struggles) while ostensibly meeting the institution’s fairly unambitious goals of teaching academic writing and research in a required lower division course, often to students who lack basic critical thinking or reading or comprehension skills, have little research and analysis experience, much less competence required for civic participation.

When did I start working here? My favorite joke has helpfully provided a short answer, and explained, perversely, poetically, why I’ve stayed as long as I have at a job which reliably delivers insulting everyday working conditions, too much work, lousy compensation, and regular threats to indeed fire me by way of absurd student evaluation (read: consumer satisfaction) criteria among other and numerous obstacles to practicing something like “radical” pedagogy. The answer is that I’ve found meaning, opportunity for authentic participation, genuine satisfaction, and camaraderie in resisting. Yes, I really started working at the university when I understood my vulnerability, and found my parallel, simultaneous work as a union activist: elected member of my union local’s board, grievance steward, committee chair, organizer of workshops and meetings and protests and parties. I honestly can’t imagine how any lecturer could otherwise explain, justify, or endure the job.

But there’s more. Recently, my joyfully ironic if stubborn joke got funnier, weirder, more poignant and dramatically applicable than even I could have imagined. In its latest telling it helped not only me but other adjuncts. After I was twice denied a request for paid medical leave (brain surgery, if you are wondering), my union leadership and fellow activists organized a grassroots campaign on my behalf, lobbying university administration to exercise its prerogative to make an exception to the Memorandum of Understanding between the UC and University Council-AFT, and grant a lecturer otherwise un-mandated paid medical leave for a serious medical condition. I am not kidding. Alas, neither was HR. The institution had interpreted our collective bargaining agreement as providing paid leave only for adjuncts teaching a 100 percent load, so that if I’d had an appointment to teach eight classes instead of my annual six, it’s possible (though not guaranteed) that I’d receive paid leave.

It’s perhaps hard to see the funny part here, unless you’ve been, like me, telling, living, and repurposing that dumb joke for nearly your entire so-called career. Honestly, I had after the school’s decision, given up. I was resigned to filing for university-provided disability insurance (a few hundred dollars every two weeks) while unemployed, living off savings and — wait for it! — paying back that portion of my fall quarter salary already deposited in my bank account before classes started, no kidding.

But here’s the glorious punch line. While I was preparing for surgery, then under the knife, and finally, recuperating, guess what? My union comrades — those who’d laughed at, been in on the joke, and also embraced and applied its existential demand for resistance — were working on my behalf.

My union president initiated an online petition meant to shame administration, successfully delivering nearly 7,000 signatures. Two members of our contract bargaining team met informally with the university to object, argue, and negotiate. My union field rep composed yet another letter, filled out required forms and coordinated with HR to ask again. One union officer contacted media, resulting in local and national stories. Another physically handed out dozens of old school photocopied flyers, and taped them up around campus, resulting in phone calls and emails.

In less than a week the Vice Provost and Assistant Vice Chancellor of Academic Personnel changed their minds, accommodating my (our) request and, yes, establishing a precedent which clearly the school had sought to avoid. Like the guy who has only a hammer for a tool, management often sees only thumbs. Until they saw solidarity, which worked to persuade them. Lately, I am told, another UC campus granted a similar exception to another seriously ailing lecturer.

I’m doing well post-surgery, thank you, and plan to teach next quarter, and return to my volunteer work with my local. Not long ago a younger colleague asked me if he should accept the conditions of limited job security offered by the university’s “continuing appointment“ job status, the closest lecturers currently can get to job security, and something like a career. Instead of applying annually for your own job, this status assures a three-year appointment. I didn’t feel I could give advice then, torn as I was between encouraging my colleague’s righteous commitment to democratic public education and the vision of struggle, maltreatment and discouragement I know awaits him.

Today I’d answer yes, to both jobs. To taking the inadequate, precarious and undervalued position as lecturer, sure, but only with the commitment to also signing up for the equally, if not even more important job — uncompensated but urgently, profoundly and absolutely required — of union activist.

When did I start working at UC Irvine? Ever since they threatened me, and I started working for and with the political activists who are my union.

—–

This article was first published in

Radical Teacher.