California schools have returned to in-person learning, but acute staff shortages are hobbling the return. The hardest positions to fill are often special education instructional aides.

For “SpEd IAs,” as they are known from early childhood programs to post-secondary classrooms, there is no “social distance” with their students. Assignments may require feeding children, changing diapers, and handling medical equipment. Emotional outbursts can also be physically punishing to paraeducators.

If that wasn’t daunting enough for a job applicant, consider the salary: SpEd IAs begin at minimum wage in many school districts, their weekly hours are often capped well below full-time, and they have limited benefits.

The COVID pandemic aggravated all those problems. The trauma special ed students faced for two years have thrown many off balance, while medical absences and the lure of better paying jobs has led to larger class sizes with fewer staff.

The result has been increased physical risks for SpEd IAs, a shakier emotional state for their students, and greater distractions for general education students trying to catch up with their studies.

CFT is addressing this crisis in the state Legislature and, on March 19, passed a resolution calling for stronger measures to recruit and retain educators, including a living wage with benefits for paraprofessionals and expanded career ladders. The resolution states that no classified employee should make less than $20 an hour and payment should be scaled up from there based on responsibilities, skills, and duties.

Meanwhile, an initiative is circulating for the November ballot to raise California’s minimum wage to $18. And AFT locals from Menifee to San Francisco are pushing for relief at their local bargaining tables.

District contracts out paras, pays them more than staff

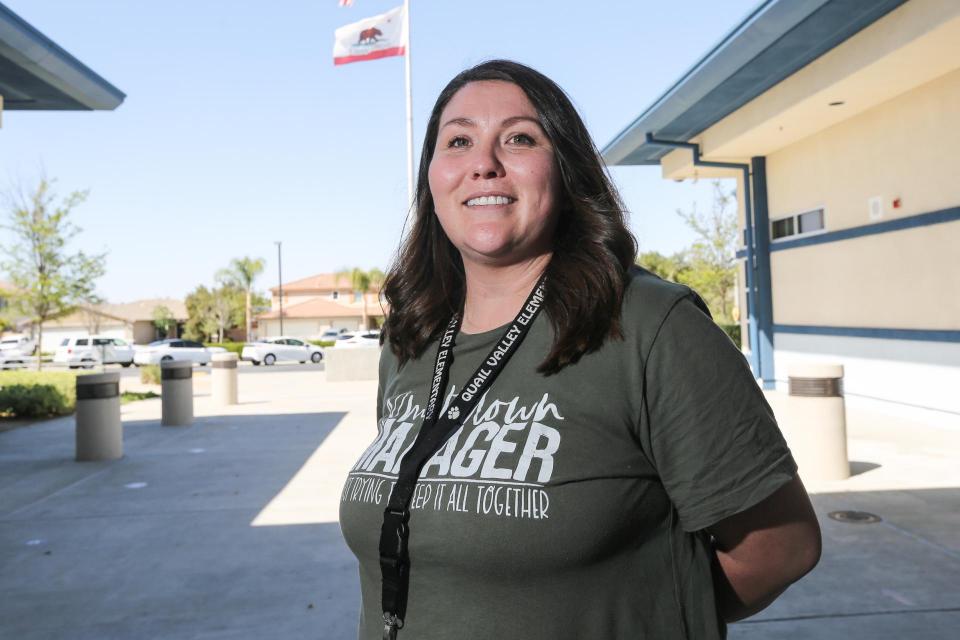

Janine Lugo has worked for the Menifee Union School District as a SpEd IA for nearly seven years, beginning with a year as a substitute. Lugo is also vice president for paraprofessionals of the Menifee Council of Classified Employees, AFT Local 6109.

About 200 IAs work in the district’s 15 schools, she said, and almost all are SpEd IAs. “And I know we need more.”

The Menifee district has been unable to fill the staff shortage, Lugo said, because salaries are too low.

“Retail clothing stores pay their people more than IAs earn,” Lugo said. “If the district wants quality people, they need to pay a living wage.”

Lugo is paid for 6.5 hours daily, and makes about $2,000 monthly. She has reached the sixth salary step, though, and is maxed out. The Menifee school board recently approved a 9.273% pay increase in stages that will be in full effect by summer.

“Those of us at the bottom are still at the bottom. I make just above $15 an hour, but it isn’t enough. Most of us can’t even afford the district health insurance plan.”

The district recently touched off a storm by contracting an employment agency to hire IAs that Local 6109 members discovered were being paid $25 per hour. The district superintendent and personnel director met with Lugo and about 20 union members.

“A lot of these women have been here for 15 years or more and love their jobs, but they’re not getting the resources they need at work or the income they need at home.”

Contract negotiations are underway and the top issue at the table is salary.

San Francisco paraprofessionals face high cost of living

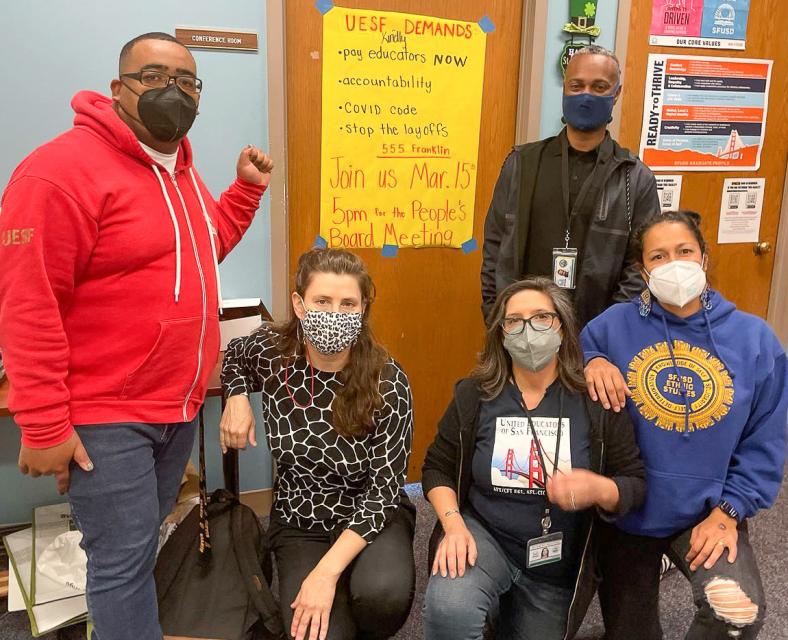

About 1,600 paraprofessionals work for the San Francisco Unified School District. Hourly wages are higher in the Bay Area, but so is the cost of living, and low pay is a major reason why the district has trouble recruiting SpEd IAs.

Sean Nunley-Willis said paras have scored major advances during the nine years he has worked for the district. Substitutes now begin at $13 an hour, and more experienced “core subs” earn $18 an hour. SpEd IAs start at $23.45 an hour, but most work only five to six hours daily.

“How do you take a job for $20 an hour, but only work five hours a day?” said Nunley-Willis, the vice president of paraprofessionals for United Educators San Francisco, AFT Local 61. “I know paras who had to resign because it’s too hard to work enough hours to survive.”

UESF negotiated a seventh salary step during the last contract, but paras must work at least 75% of the school year to advance. That can be difficult when staff don’t work during summers, winters, or Thanksgiving breaks.

Wages were clearly the main concern in a recent AFT Local 61 bargaining survey, and negotiations will begin this summer.

Nunley-Willis became a para completely by accident. He was working in an afterschool program and it was looking for substitute SpEd IAs. He took a long-term, one-to-one assignment working with a child with serious behavior issues.

“I have been bitten and head-butted but it’s not because these are bad kids. Sometimes they can’t process their emotions. They don’t know how to regulate themselves.”

SpEd IAs can’t maintain social distance, he said, especially if the child has disabilities.

“Depending on their grade level, some kids like a hug in the morning, or want to hold your hand when they walk through the school. It’s part of the job, but it is an increased risk.”

Gilroy loses many in para ranks, class size nearly doubled

Gilroy schools lost more than 30 of their 165 paras during the pandemic.

“The shortage is across the board,” said AFT Local 1921 President Ramona Bañuelos. “Those short staffs have meant larger classrooms. My room has grown from eight to 14 students.”

Bañuelos began working with the school district as a yard supervisor 14 years ago, and has been a SpEd IA for the past eight years.

Many returning students forgot social skills while they were at home. “Being out of class for so long, the kids are learning how to live in a new normal,” she said. “We need to learn how to give the kids the support they need.”

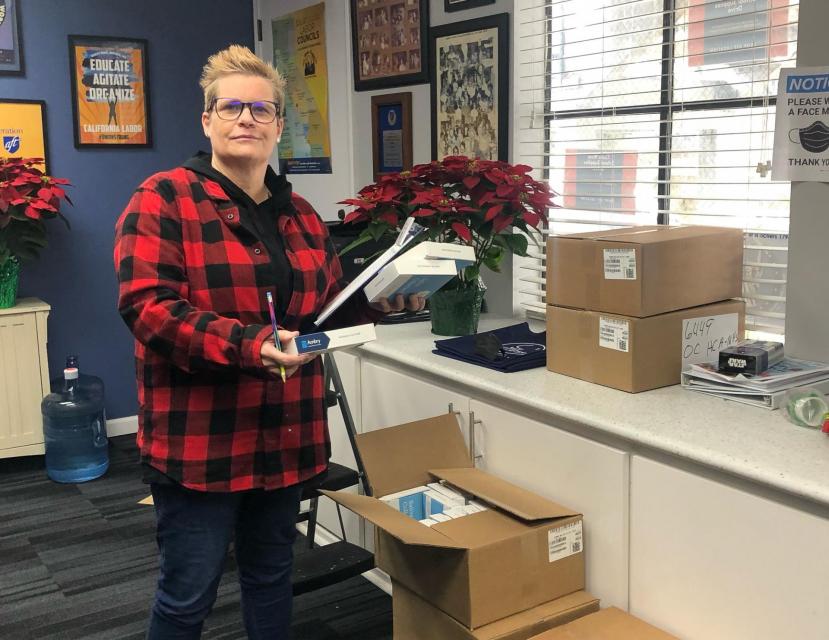

Arti O’Connor led the Gilroy Federation of Paraeducators for 10 years, and continues to serve as a CFT Vice President. The 20-year veteran worked with K-8 students, mostly as a special ed resource paraeducator, an academic position. She taught small groups of special ed students within general education classrooms.

“The educational system can’t function without the classified staff,” O’Connor said. “If we were gone, you couldn’t help but notice it.”

Since stepping down last July, O’Connor has worked closely with Bañuelos, incoming Secretary Rachel Vizzusi and Treasurer Jacquelyn Stevenson. All three are SpEd paraeducators in elementary schools.

Leading the local union during the pandemic, Bañuelos said, “has been like riding a bucking bronco.”

Ventura paras see changed behavior in returning young adult students

Cindy Escareno works with post-secondary students from 18 to 22 years old for the Ventura County Office of Education. Escareno teaches life skills, from riding public transportation and shopping within a budget, to washing clothes in a coin-operated laundry. Some of her students take classes at Ventura City College across the street.

“Our students are typical kids,” she said. “They know what’s going on around them. They know stress. When we came back to school, there were some kids whose behavior had changed so much that I didn’t recognize them.”

Escareno, who heads the Ventura Federation of Paraeducators, and a second SpEd IA assist a teacher and eight students. “That’s the minimal amount of staffing. We often get extra support if student behavior calls for it.”

The local represented nearly 300 paras until the Ventura Unified School District took back care for its middle and high school students, resulting in dozens of layoffs. SpEd IAs were hit hardest.

AFT Local 4434-1 is also getting ready for contract negotiations. Pay raises are the main focus.

Escareno was a stay-at-home mom for 13 years, until a child was born with cerebral palsy and she dived deeply into caring for children with challenges.

“When I started 17 years ago, I had no idea how much this job would become part of my life,” she said. “You go from caring for one child to caring for a classroom full of children.”

— By Steve Weingarten, CFT Reporter