Members, officers, and activists from higher education unions throughout California came together for a full day during Campus Equity Week to chart a strategy for defending public higher education. They denounced especially the way education institutions, under corporate pressure, increasingly rely on contingent instructors while treating them as outsiders.

Members, officers, and activists from higher education unions throughout California came together for a full day during Campus Equity Week to chart a strategy for defending public higher education. They denounced especially the way education institutions, under corporate pressure, increasingly rely on contingent instructors while treating them as outsiders.

“We are not add-ons,” declared Marianne Kaletzky, from Berkeley’s AFT Local 1474 of the University Council-AFT, as she opened the conference. “We are essential to teaching and to the mission of our institutions. We have to resist the pressure to think of ourselves as some kind of second-tier educators. Students are paying more, but their rising tuition doesn’t go to improved teaching or education. By talking with them about this, we are providing an important part of their education, giving them knowledge they’ll need to go forward in life as workers.”

The late October conference, convened at Berkeley City College, was sponsored by a diverse group of education unions representing faculty in Northern California, including AFT community college Locals 1603 (Oakland), 2121 (San Francisco), 1493 (San Mateo), 4400 (Cabrillo) and 1533 (Fresno), together with UC-AFT local unions and the California Faculty Association. The meeting took up the challenge of the national Campaign for the Future of Higher Education, launched almost a decade ago.

Eight years ago faculty from across the United States joined together on the anniversary of the Brown vs. Board of Education decision, “to inject rationality and human values into the discussions taking place about how to ‘reform’ higher education.” The campaign warned against the “standardized, simplistic metrics,” used to attack teachers and unions, and hollow out K-12 education. It called for countering corporate reforms, advocating for inclusive and affordable higher education with a diverse curriculum, protection of academic freedom and terms of faculty employment, and substantially more public investment.

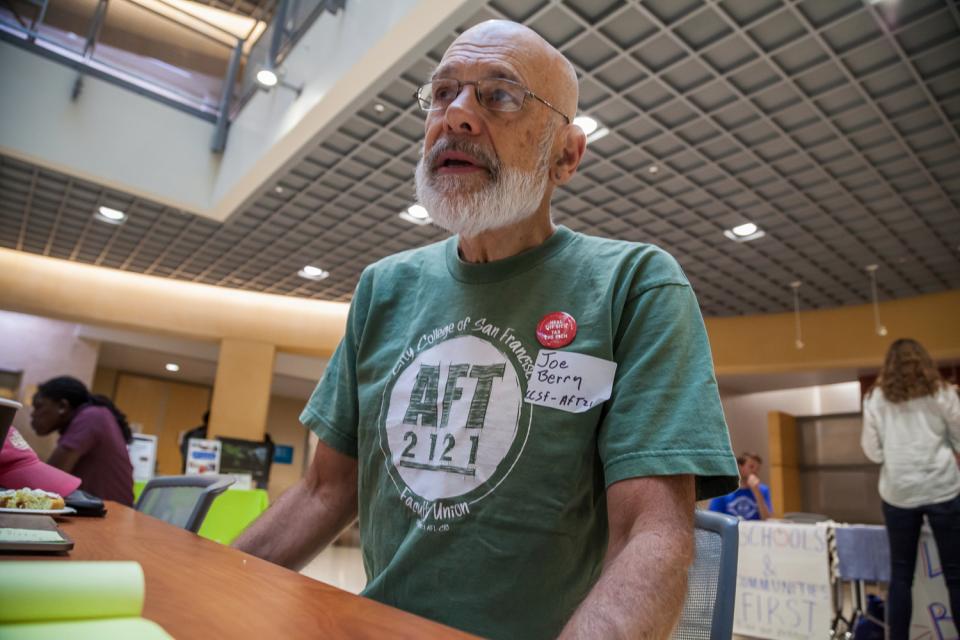

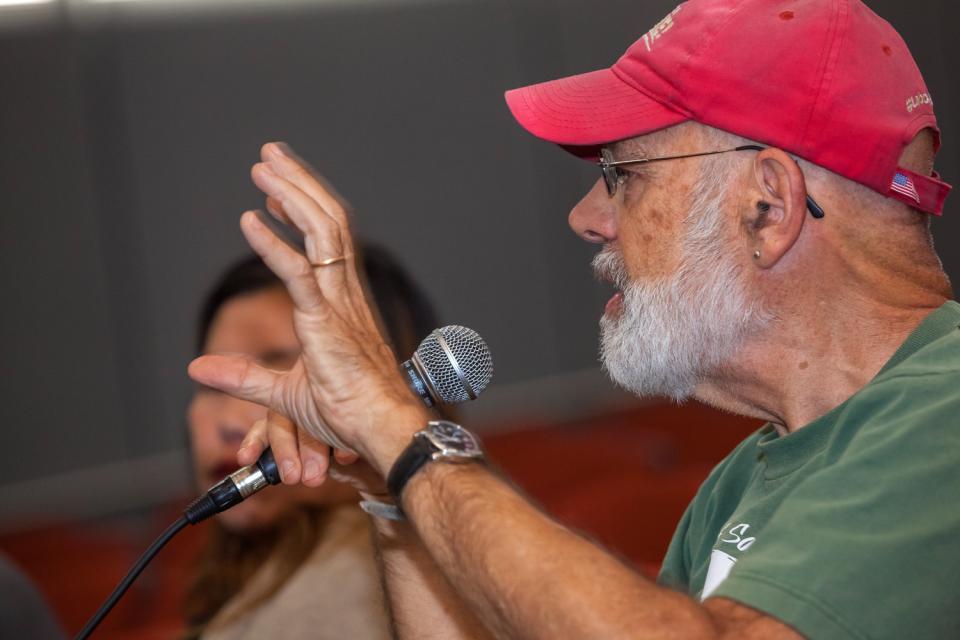

Joe Berry, who teaches labor studies and history at City College of San Francisco, explained that the daylong October meeting continued the same movement against the “neoliberal agenda of private corporations.” In community colleges that agenda seeks to shrink the number of full-time faculty, he said, substituting the employment of increasing number of contingent instructors, and to narrow the scope of higher education itself to vocational preparation and transfer to four-year institutions.

“It really takes the community out of community college,” Berry charged. “Although we won our fight over accreditation at City College, it came at a high cost, with enrollment reduced from 100,000 students to 60,000. And while the trustee is gone, the administrators brought in who are loyal to that agenda are still here. And because we led the opposition to it, we’re still attacked.”

While the union, AFT Local 2121, helped elect a majority to the board, “Even those we elected are subjected to tremendous pressure once they’re in office, with boot camps putting out these corporate ideas,” Berry explained. “They get much less from our side. We don’t depend on structure and money, but on people. But it’s hard to keep people mobilized on a constant basis.”

Speaking at the opening plenary, Paul Bissember, executive secretary of the San Mateo Community College Federation of Teachers, AFT Local 1493, expressed the admiration common among all the participants for the growing educators movement and strikes around the country. He cautioned, however, “We don’t have the same level in higher education. We need to build a network to meet that challenge.”

Blanca Misse, from the California Faculty Association at San Francisco State, reinforced that idea, noting that “in the radical Bay Area we usually don’t even know each other.” She applauded CFA for being one union for everyone, but cautioned that “we have to look at the inequalities that exist even in our own union.”

To discuss this challenge, the conference took up three themes: academic freedom; the growth of contingent labor; and the struggle against the oppression of women, people of color and LGBT faculty.

I-Wei Wang, a librarian at UC Berkeley, explained that her statewide union, UC-AFT, broadened its base of support by challenging the administration when it said that librarians were not entitled to the protections of academic freedom. “You could say we lost that fight since we didn’t get a clause in our contract to specifically include us, as the lecturers did,” she told the working group on academic freedom.

“But we had a much larger win,” she said. “The university had to agree that academic freedom applies to all academic personnel. And our fight became a way to engage with our own members, so that they saw the union as more than just a place to go when you have a problem, but as an organization protecting rights that are important to them. And because the university didn’t want to include academic freedom in negotiations, they had to talk much more than they wanted about the basic contract issues of wages and conditions.”

In the anti-oppression working group, Elyse Banks, a teacher at the University of San Francisco, criticized the kind of tokenization she said faculty of color are subjected to in dialogues with administrators. “We wind up being advocates for students and helping them build community, but aren’t compensated for this, and often we’re just ignored,” she said.

This theme was elaborated by Anibel Ferus-Comelo, a lecturer at UC Berkeley. “Students of color feel discriminated against, so they congregate around faculty of color,” she explained. “So we feel besieged as students gravitate for support, validation and a feeling of belonging. I’ve had students who have suffered criticism of their writing in other classes. This isn’t about standards; it’s because they convey their ideas in a way that white students and instructors can’t accept.”

Ferus-Comelo suggested that a commitment to student diversity, equity, and inclusion means that institutions have to hire more people whose function it is to serve students, and noted that this is also the demand in teacher strikes like the recent one in Chicago. “One person — one — was hired at Berkeley to serve the ‘basic needs’ of students on this whole campus. We have students who are unhoused and hungry. Yet the university contracted out food service to a private contractor that raised the price of meals in the cafeterias. What we need is a reordering of the university’s priorities.”

In her analysis, “there is a material basis for oppression in public higher education.” The rise in tuition and student debt, for instance, impacts low-income and working class students much more than others. Instructors of color and women are overrepresented among contingent faculty. A small percentage of high salaried administrators receive a higher proportion of payroll than the bottom 50 percent. “And the impact of Proposition 209 is that we can’t talk about this. We can no longer talk about race in admissions and hiring. But being ‘race blind’ doesn’t work.”

In the working group on contingent labor, Keith Ford, from the State Center Federation of Teachers, AFT Local 1533, at Fresno City College, talked about the shame experienced by some part-timers, as they can’t realize their dreams of permanent steady jobs or a decent salary capable of supporting families adequately. “We got degrees, and believed that education leads to a better life,” he said bitterly. “That’s what we told our students. So what do we say to them about our real situation? We have to transform that shame into anger.”

Chris Cox, a CFA member at San Jose State University, recalled that as students “we thought we wouldn’t get rich teaching, but we wouldn’t live in poverty either.” Yet after teaching for 23 years, “how much of a fool was I to think that opportunity would finally come? It’s when I got involved in my union that I started to feel empowered, and the level of my professional development began to rise.”

Brad Erikson, a lecturer at San Francisco State, charged that “between 1993 and 2009 universities added 10 times more administrative positions than tenure line positions, giving them the lion’s share of resources.” He described the institutional means by which lecturers are kept in inferior positions, from pay gaps to slow rates, if any, for advancement.

He charged especially that student evaluations, given much greater weight in evaluating contingent faculty, “demonstrate gender and racial bias in favor of white men, and produce racial and gender disparity in hiring, retention or advancement, violating the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Newly hired lecturers are disproportionately people of color, and lecturers have always been disproportionately female.”

Erikson put forward a set of demands that could be included in contract negotiations, including greater tenure density, conversion of lecturer lines to tenure lines, salary equity measures and step system parity, among others.

These demands were widely discussed and supported. Open bargaining was proposed as one of the most important ways to not just bring them before administrators in an effective way, but as a means to unite faculty and inspire them to take action.

Lecturers at UC-AFT, whose contract expires in January, have opened up bargaining so that anyone can come in. “We were inspired by the librarians, who won a 22-26 percent raise, and did it by organizing,” declared Emily Rose, field representative for UC-AFT in Berkeley. Chris Cox agreed, concluding, “Our gains come from organizing.”

— By David Bacon, CFT Reporter