Editor’s note: With uniquely linked histories, the CFT and AFT Local 61 both celebrate their 100th Anniversaries in 2019. What follows is a capsule history of the oldest local union in the California Federation of Teachers. From the search for true union representation in 1919 to the quest for affordable housing for union members 100 years later, the history of AFT Local 61 — the United Educators of San Francisco — is one of proud support for educators, their unions and students.

By Dennis Kelly

PART 1: Local 61 – The beginning

When the San Francisco Federation of Teachers formed in 1919, there were already nine existing teacher organizations in the city. But none of them was a union.

One organization called itself a federation, but it was not affiliated with the San Francisco Labor Council. The San Francisco Classroom Teachers Association (1917) was dominated by administrators and preferred to be known as an Association. There were High School Teachers and Teachers’ Councils. The most militant organization was the Teachers Association of San Francisco — in 1917 it grew out of the Kate Kennedy Teachers Clubs (1911) and was led by Margaret Mahoney, but it also shied away from joining with labor.

J.P. Utter founded the first California local union of the American Federation of Teachers in 1918 in Vallejo. He urged other teachers to join the AFT, and affiliate with the local labor council. He believed that teachers could speak through the labor council and have allies and an enhanced voice.

Seven high school teachers in San Francisco took up the challenge in April of 1919. They submitted the request for a charter and promised to enlist others. By the end of the month they had 60 members. Paul Mohr was the first president and Edward J. Dupuy was in charge of organization according to Harriet Talan’s invaluable masters thesis on the first 40 years of Local 61.

One of the first decisions they faced was how to structure their organization and who should be members. The national AFT urged them to keep Local 61 as a union of high school teachers and to work on the creation of an elementary local that would appeal to women.

John O’Connell, the head of the San Francisco Labor Council, urged something else: keep one local and include elementary and high school teachers, men and women. Presaging the inclusivity that has been a hallmark of the local, the founders of Local 61 decided to build one strong union for all of San Francisco’s public school teachers.

By the end of the school year Local 61 had grown to over 100 members.

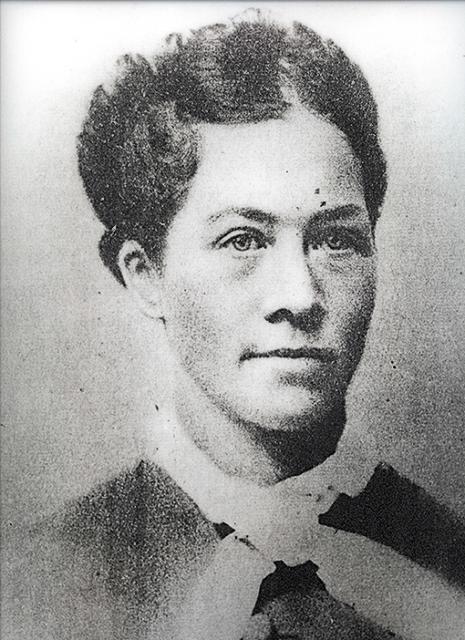

PART 2: A founder – Edward J. Dupuy

We don’t know much about the founders of Local 61, but one of the first members gives us some insight into the early days of the union.

Edward J. Dupuy was a French teacher at Girls High. In 1919 he was a founding member of the local and chairman of the Organizing Committee. Despite the AFT’s requirement that any group wishing to be chartered as a local had to have a minimum of 10 members, Dupuy sent in only seven names from San Francisco, but promised more. The local aimed at 500 and hoped to recruit some women, too.

By the end of the school year, membership had grown to 100, Paul Mohr was the first president and Anne Crowley was selected as the local’s first vice president.

In 1920, with the local only a year old, district Superintendent Alfred Roncovieri began a purge of union members who were teachers. This official hostility had the effect of suppressing the membership. However, E.J. Dupuy kept the union flag flying. Between 1920 and 1923 he appeared on radio to speak for unions and traveled throughout the state, as far away as Los Angeles, to help organize new locals.

By 1926 there were 12 outstanding complaints about pay in San Francisco schools, but no contract and no grievance process. Superintendent Joseph Gwinn unilaterally withheld pay that teachers had earned if he had reason to believe they would not return the next year.

Despite the existence of several teacher organizations, the absence of collective bargaining and a recognized union made it difficult to confront these injustices. Dupuy, who was a dual member of AFT Local 61 and the California Teachers Association, decided to do something about it himself. He filed suit on behalf of the teachers and won two settlements, the first for $600,000 and a second one for $190,000.

Dupuy’s advocacy brought attacks from the superintendent and rumors of spies at Girls High who were charged with snooping on Dupuy. Superintendent Gwinn lashed out at Dupuy, but a few years later the superintendent was charged with financial irregularities and had to resign.

According to Harriet Talan’s early history of Local 61, John O’Connell, head of the San Francisco Labor Council, threatened he would call a strike of every union in the city if Dupuy was removed from his assignment.

Edward J. Dupuy helped to establish the reputation of Local 61 as a union dedicated to the fight for justice. He joined the district in 1899 and served until his death in 1937. Local 61 President H. P. Dole referred to him as a “jolly-natured Frenchman,” a man of considerable charm and a popular reputation for taking on school administrators.

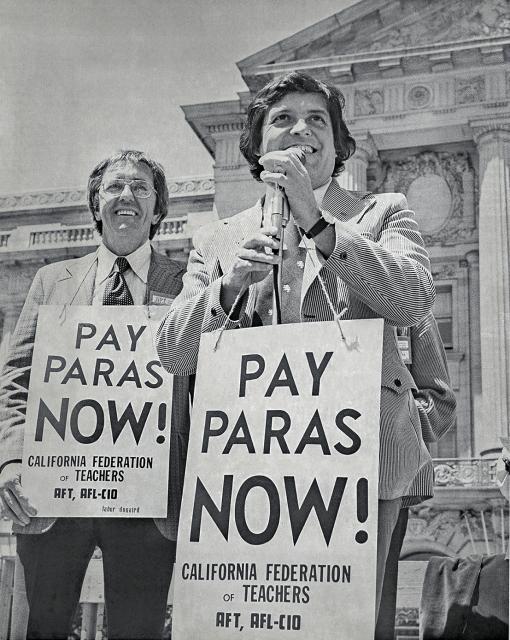

PART 3: Jim Ballard

James Edward Ballard was an elementary teacher specializing in math. A navy veteran of World War II, Ballard hailed from Kentucky and had worked in the United Auto Workers before coming to teaching. In the mid-60s, Jim Ballard was hired as the field representative for the San Francisco Federation of Teachers, AFT Local 61. Two years later he was elected president of the local.

Jim Ballard brought the local union into the modern era. He followed men who were committed to the union and were great spokespeople for teachers, Al Tapson and Dan Jackson. What Ballard added was organization and a sense of the necessary discipline to get the job done.

Under Ballard, the SFFT took a militant edge. The city was divided into 10 areas and a feeder system was developed for the distribution and collection of information. Ballard presided over the organization of paraprofessionals into a separate bargaining unit and led Local 61 on four strikes in 1968, 1971, 1974, and 1979.

Ballard was the union president at the time of Proposition 13, a California ballot measure that changed the way taxes were collected, and destabilized education funding necessitating more than a generation of struggle and catching up.

Ballard’s presidency was marked by intense rivalry between the San Francisco Federation of Teachers and the San Francisco Classroom Teachers Association. The 1975 passage of the Rodda Act granting collective bargaining rights to certificated employees meant that the winner of the rivalry represented all the teachers.

Local 61 won the first representation election in 1977. SFCTA won a subsequent one in 1981, after the six-week strike of 1979. SFCTA claimed the dues deduction apparatus and Local 61 was on the verge of going out of business. But Ballard mustered his organizational abilities and Local 61 continued by collecting dues through its affiliated credit union. This meant approaching the entire membership and convincing them to sign up in the union again.

This feat, plus representation of the paraprofessionals, kept Local 61 alive until 1989. At that time the local won back collective bargaining rights for teachers and jointly formed the merged United Educators of San Francisco.

Jim Ballard stepped down from the presidency in 1984 and was succeeded by his vice president, Joan-Marie Shelley.

PART 4: Strikes

The San Francisco Federation of Teachers, Local 61, has led four strikes. Three of them came before the existence of collective bargaining for educators. Only one, in 1979, came under the rubric of the Rodda Act. The strikes were in 1968, 1971, 1974, and 1979. Each one was longer than the previous one.

The 1968 strike lasted only one day. Local 61 President Jim Ballard liked to tell the story of negotiations. “We don’t have to bargain with you,” the district said, “there is no law that commands it.” Then after the one-day strike, the tune was changed to “There is no law that says we can’t bargain with you, so we will.”

That strike saw a commitment to affirmative action hiring to integrate the teaching corps, the added benefit of a dental plan, pay raises, and a limit on class sizes.

The strikes of 1971 and 1974 were longer, four days and seven days, and less productive.

The strike of 1979 came after San Francisco Unified tried to make sense of Proposition 13. Over 2,000 teachers were laid off, cutting back to people with 10 years of seniority. Lay-offs for about 1,000 were rescinded and the final thousand were to come back on a temporary basis, subject to dismissal any day by the notification of the human resources department.

That strike took place at the beginning of the school year. As it dragged on support wavered. When teachers went back into the buildings, the superintendent added another destabilizing element, massive transfers that moved many teachers all around the city. As a result of the strike most of the final thousand laid-off teachers were brought back to work on permanent status.

Two years later, the SFCTA won a decertification election and Local 61 did not represent teachers in San Francisco until 1989.

PART 5: Joan-Marie Shelley

Joan-Marie Shelley was born into a union family on June 15, 1933. Her father was a teamster in the Bakery Wagon Drivers local who moved on to become head of the San Francisco Labor Council and the state labor federation. He was subsequently elected to the state Senate, then Congress, and finally mayor of San Francisco.

In her early years, Joan-Marie Shelley went to school in San Francisco, attending John Muir, Sherman, Commodore Sloat, and Jefferson. She then went to Lowell High, to Stanford University, and to France on a Fulbright.

Shelley started teaching in San Francisco in 1955 at Mission High, before putting down roots at Lincoln High, then transferring to Lowell.

For 15 years Shelley was a dues-paying member and took no other elected role in the union. But then her ascent was rapid. Joan leaped from member to building rep and area rep, on to strike captain (1971), then got to do that again in a second strike (1974). Next she was voted in as vice president, and in 1984 she succeeded Jim Ballard as president of the San Francisco Federation of Teachers, Local 61.

Shelley led the union defending against a challenge for the paraeducator unit, then mounted an unsuccessful attempt to take bargaining rights from the CTA, and finally, in 1989, Joan led the victorious attempt to reclaim the role as teachers’ collective bargaining agent.

The collective bargaining victory created the platform on which to unite the two rival organizations — SFCTA and SFFT — and create the union we know as the United Educators of San Francisco.

The elimination of organizational rivalry meant that the UESF could finally face the administration as a unified force. This began a new era for the membership of Local 61.

PART 6: The Merger – 30 Years of Unity

A joint dinner of the Executive Boards of the SFFT (Local 61) and SFCTA was held in 1977 under the leadership of Pat King (SFCTA) and Jim Ballard (SFFT) to propose a merger of the teacher unions in San Francisco.

The effort died when the parent unions could not agree on terms for coming together. A decade of expensive and divisive collective bargaining representation elections followed with each union spending time as the teachers’ collective bargaining agent.

When Local 61 won back collective bargaining rights for the teachers of San Francisco in 1989, the path was laid for merger of the competing teacher unions. The eventual merger put to rest a decade of intramural warfare. Roughly a third of the teachers were members of each organization and a third were unaffiliated. Management was able to play off one organization versus the other and it was difficult for either side to accomplish the kind of strength needed to win a good contract.

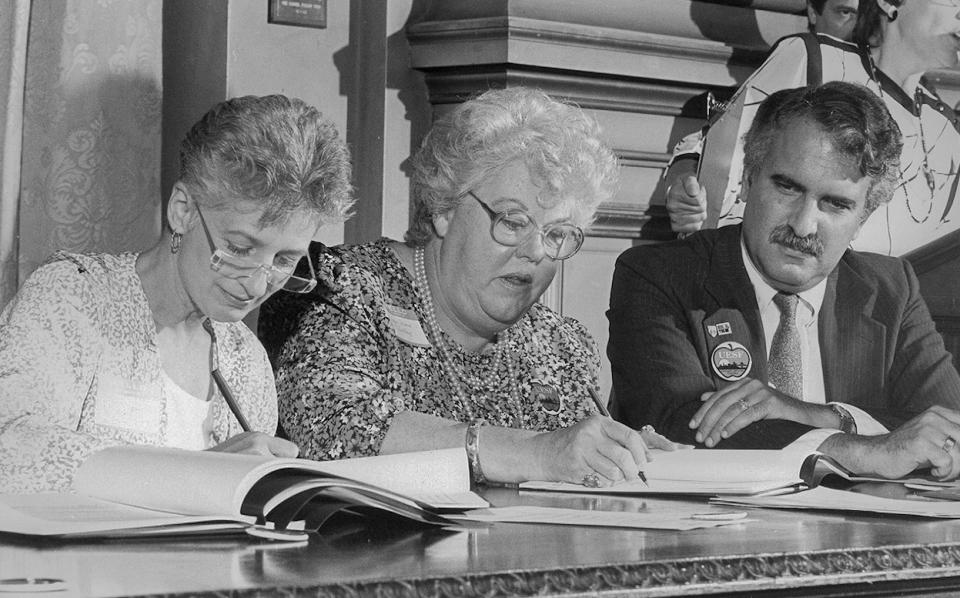

Local 61 President Joan-Marie Shelley offered merger to the SFCTA and its president, Judy Dellamonica. With the support of CTA state leadership, (President Ed Foglia and Executive Director Ralph Flynn) and CFT President Miles Myers, this olive branch was accepted and local leadership sat down to figure out how to work together. There were no merged states and only one merged local (Rosemount, Minnesota) that used the full merger model that would become UESF.

The state and national parent unions agreed that they would grant full representation, but accept half dues for all the members in San Francisco. This would end the expensive collective bargaining elections and create stability and strength in the union. Every teacher would be a member of UESF, AFT, NEA, CFT, and CTA.

Teachers who had philosophical or other reasons for not belonging to one of the affiliates would still maintain membership in UESF and the other affiliates. There was no financial incentive not to belong. Joan-Marie Shelley wrote in “Unity, Strength, and Merger” that there were 13 SFCTA members who chose not to join AFT and 13 SFFT members who did not join NEA.

Larry Halling (SFFT) chaired a joint constitution and bylaws committee that successfully created the governing documents for UESF. A transitional executive board was carved from the two existing unions with the SFCTA president serving as UESF vice president.

PART 7: Paraeducators

When teaching was a solely male occupation, the watchword was that the teacher had to be strong enough to physically control the largest boy in class. A great deal of progress has been made since that time.

The 1965 “War on Poverty” of the Lyndon Johnson presidential administration authorized classroom support directed to children living in poverty. That support most often was embodied in a paraprofessional classroom aide who shared some of the classroom responsibilities with the assigned teacher.

In San Francisco this new job classification was ensnared in a web of complexity that the school district exploited. Caught between city civil service and temporary status under the Title I injunction to supplement, not supplant local efforts, the paraeducators became vulnerable to annual layoffs and had no guarantee of a job.

In 1972 Local 61 opened its membership to paraeducators (then called paraprofessionals). Early leaders included Linda Cook, James Nethers, Gloria Washington, Wesley Williams and Aracelly Martinez. San Francisco Unified denied that they were the employers of the paraeducators until a 1977 ruling by the Public Employment Relations Board settled the issue. Until that time, these district employees had no civil service protections, no movement on the salary schedule, no paid vacation, and no dental plan.

Paraeducators won their first contract in 1977. By 1979 their benefits included a salary schedule, and medical coverage if they worked a four-hour day. The PARS retirement program was put in place as a stop-gap, and was not removed for more than two decades. At that time paraeducators were moved under the umbrella of Social Security. Paraeducators are also beneficiaries of an annual bonus generated by the parcel taxes.

Local 61 changed its structure in 1981 to include a vice president representing paraeducators. Peggy Gash became the first person to fill that position and go on union staff. Gash was succeeded by Bradley Reeves and Carolyn Samoa according to UESF’s booklet, “Paraprofessionals and their Union.”

In 2005, CTA finally voted to accept paras as members, making their inclusion in the union family complete. Locally, the mayor’s office now recognizes a Paraeducator of the Year in addition to the teachers and administrators who are recognized annually.

PART 8: Parcel Taxes

The passage of Proposition 13 in 1978 meant that school funding would have to be re-thought. School districts lost their ability to tax and California plummeted from one of the states with the highest per capita investment in education to one of the lowest. Layoffs and threats of layoffs became an annual spring ritual. This coincided with the advent of collective bargaining for educational employees.

In negotiations for 2003-04, the district complained again that it did not have enough money for significant raises, but agreed to contractual language that committed the district to attempting a parcel tax for increased revenue. In negotiations of 2008, UESF activated that language. After supporting several bond elections for maintaining the schools, the local demanded that the next effort be for the benefit of educators.

A separate bargaining team of five people (Linda Plack, Armen Sedrakian, Carolyn Samoa, Ken Tray, and Dennis Kelly) was created and the union side was determined to learn from the mistakes of other locals which had opposed their local parcel taxes because of distrust of their district administrations.

UESF’s answer was to jointly create a spending proposal for the parcel tax and put that plan into the contract. Like contractual matters, the spending proposals of that first parcel tax were under constant scrutiny by the union.

The 2008 parcel tax was passed by the electorate and raised the floor of the pay scale to $50,000, created a variety of bonuses and awards recognizing teacher scarcity, longevity, and whole school awards for school-wide projects.

A second parcel tax was put on the ballot in 2018. Both parcel taxes have a 20-year life span and must be renewed by another vote. As of this writing, the 2018 parcel tax has been challenged based on interpretations of legislative changes to the passage rate, and is still awaiting a final verdict.

PART 9: UESF and Housing

On election day in 2019, the voters of San Francisco passed a measure that made it easier to build housing for the city’s educators. This measure streamlined and consolidated some of the difficult restrictions and regulations that had impeded educator housing in the past and brought to a conclusion more than 15 years of striving by UESF.

During the presidency of Kent Mitchell (1997–2003), San Francisco Unified offered to co-locate some housing for teachers on the site where a new school was being built. Although the union saw it as a good first step, the membership rejected the offer as too little and a failure to address the need for both salary and housing on the part of the whole union. Nothing was offered for paraeducators.

In 2004, when Dennis Kelly was president of the union, the board of education passed a resolution committing excess property to educator housing, now including paras. Proposition 39, giving charter schools access to surplus school property, complicated that phase of the effort.

In 2014, the late mayor, Edwin Lee, stepped in when it was clear to him that the school district was allowing its mantra (“We are educators; we don’t want to be landlords.”) to interfere with a full-scale effort to create workforce housing. The district had hired a for-profit company to handle its property, traded buildable sites to the city to acquire title to the board’s parking lot, virtually gave others to non-public schools, and failed to make any progress toward housing. Mayor Lee sought to change all that.

During the tenure of Lita Blanc as UESF president, an agreement was reached between the city, the schools, and the union to develop the campus of a former elementary school for housing. The 2019 passage of Proposition E, under the UESF presidential tenure of Susan Solomon, means that there is rising hope for a continuation of the building begun at the one site and the further implementation of educator housing on a variety of parcels within city limits.

Conclusion

Because of their uniquely linked histories, the CFT and AFT Local 61 both celebrated their 100th Anniversaries in 2019. The AFT honored the 100th year since the founding of Local 61 at the CFT’s own Centennial Convention on March 22.

Later in the year, on November 17, the UESF community gathered in the city to celebrate the triumphant history of Local 61 and United Educators of San Francisco. All anticipated with relish the challenges and achievements of the next 100 years.

About the Author

Dennis Kelly has been an AFT member since 1968. He is the former president of United Educators of San Francisco, AFT Local 61, a former CFT Vice President and former AFT Vice President. Kelly was honored with CFT’s highest honor, the Ben Rust Award, in 2018.

As the union’s Parliamentarian for 34 annual CFT Conventions he has served under six CFT presidents—Raoul Teilhet, Miles Miles, Marvin Katz, Mary Bergan, Marty Hittelman and Joshua Pechthalt.

Kelly has an abiding interest in union history. Local 61 is the oldest AFT local union in the California Federation of Teachers, with both CFT and Local 61 observing their 100th anniversaries in 2019. Kelly has written histories for both centennial celebrations.