Yajaira J. Cuapio has been a social worker in the San Francisco Unified School District for eight years. With the pandemic, she says the last couple of years have been challenging.

“Students have been isolated for so long that it’s having an impact on their social skills. They’re arguing and fighting, and it leads to unsafe interactions,” she said. “Then academically there have been disruptions. For one thing, a positive COVID case would cause students to have to quarantine for 10 days, and if they’re out that long, truancy is established.”

Students as well as staff and teachers had loved ones die of COVID, Cuapio says.

“That’s a lot for any human being, especially younger ones,” she said. “It really impacts their mental health, and we saw an increase in suicidal ideation.”

Staff and teacher shortages have also made things hard, Cuapio says. If the district was fully staffed, she’d be doing her full-time job of training other social workers in responding to crises and providing grief counseling, but as it is, she does that along with working as the social worker at an elementary school.

Why don’t they hire another social worker? Because the district has no one in the candidate pool now, Cuapio says. She thinks this is partly due to SFUSD’s difficulty in getting people paid on time.

“The district has gotten a bad reputation for not meeting basic economic needs,” she said. “I’m on the union executive board, and I’m getting texts from people telling me they’re moving out of the district. People are dealing with the stress of not being respected, and it’s been a lot on our mental health.”

She says UESF wants a few things to make sure students get the schools they deserve—fixing ongoing payroll problems so people get paid on time, the superintendent continuing to listen, bargaining in good faith, and assurances that if more money comes in, the district will consider wage increases.

In a significant victory for members, United Educators of San Francisco just won a 6% salary increase for teachers, paraeducators, and substitutes. The union also won 45 minutes of prep time weekly for TK-5 educators and 30 minutes for secondary level educators.

“We weathered a pandemic in understaffed schools, and teachers addressed the need with compassion,” Cuapio said. “We need fully staffed and fully funded schools. There’s only so much disrespect we can take.”

* * * * *

The school psychologist at Deborah Robledo’s elementary school, also has to split her time—in her case between two schools. A resource teacher is in the same position.

This is hard on them as well as the other teachers and the students, says Robledo, a fourth grade teacher with El Rancho Federation of Teachers.

“They’re some of the most important staff members we have here, she said. “We’ve had shortages in support staff as well. Sometimes the custodian is out and the principal pitches in and throws out trash.”

These shortages have an emotional toll on the students, Robledo says.

“Students have high anxiety, and the mass shootings at other schools didn’t help,” she said. “They’re full of stress with being at home all the time and coming into the classroom without enough helping hands is affecting them.”

Everyone feels overworked, Robledo says.

“We’re exhausted, and morale is not as high as it should be,” she said. “We’re underpaid and underappreciated.”

There haven’t been a lot of teacher absences this semester, but last year, with the shortage of substitutes, a class would be split up and go to different teachers when one is out, Robledo says.

* * * * *

When a class doesn’t have a substitute at the middle school where he works, other teachers miss their prep period to fill in, says Salinas Valley Federation of Teachers member Charles Lonero.

His school is also short on support staff. Lonero says they were told at a faculty meeting that someone had been hired who would be in the office to greet parents, students and school staff. There’s still no one in that position.

Lonero, a history teacher, has been at the school for 20 of the 23 years he’s taught. Turnover is so high that he says he doesn’t know about 60% of the teachers at his site. Salinas has become an expensive place to live, he adds.

“A lot is the pandemic, and a lot is competition about the pay,” he said about the high turnover. “I had a couple colleagues from Fresno, and they were getting paid more here, but they moved back because it’s cheaper to get a house there. Here some people can only afford to rent a room.”

Both Lonero and his wife, who’s also a teacher, are wondering how much longer they will stay in the profession.

“I think these last three years have been some of the hardest,” he said. “First there was distance learning and then we came back, and it was a different kind of hard.”

Part of it is the disrespect some people have for teachers, Lonero says, and how they hold them responsible for schools shutting down due to COVID.

“It used to be teachers were respected,” he said. “Now it’s kind of wearing on both of us. It used to be ‘I can’t believe you’re a teacher, thank you so much.’ Now you don’t feel that.”

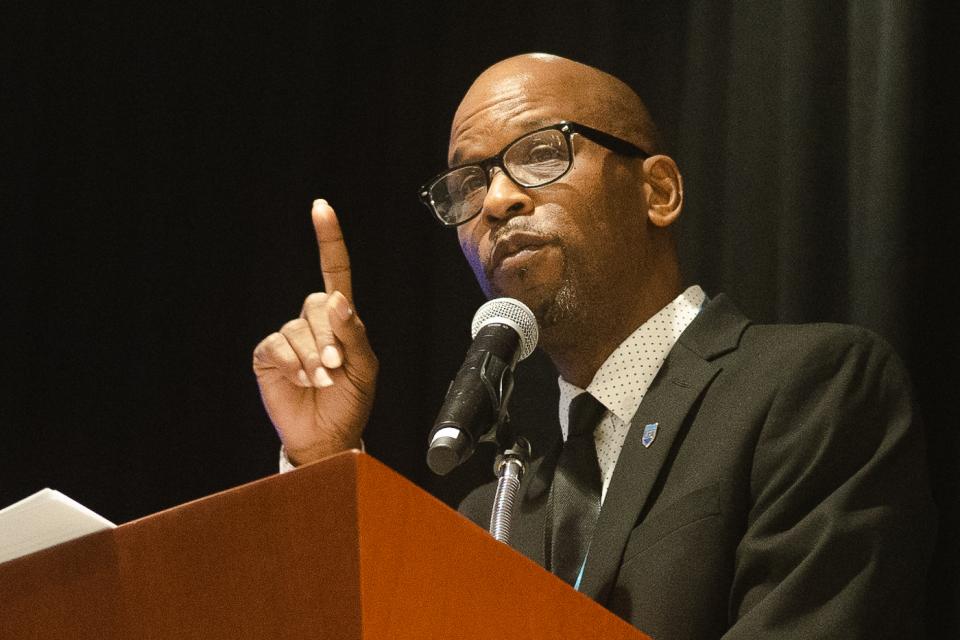

This sort of disregard for their work is a big part of why teachers and staff are leaving the profession, according to Ray Gaer, CFT vice president and leader of the ABC Federation of Teachers.

Gaer served on the AFT Teacher and School Staff Shortage Task Force that produced a report released this summer at AFT Convention. Task force members did one-on-one interviews with people to find out why they are leaving and what can be done.

“We learned it’s not just about bread-and-butter issues like compensation and health benefits,” Gaer said. “It’s also about being valued. People want to be supported in their workplace.”

Gaer says they found mental health was a big factor in people quitting jobs in education. One of the goals in the report is to make sure that state and federal agencies understand it’s a priority to have mental health services available to educators.

* * * * *

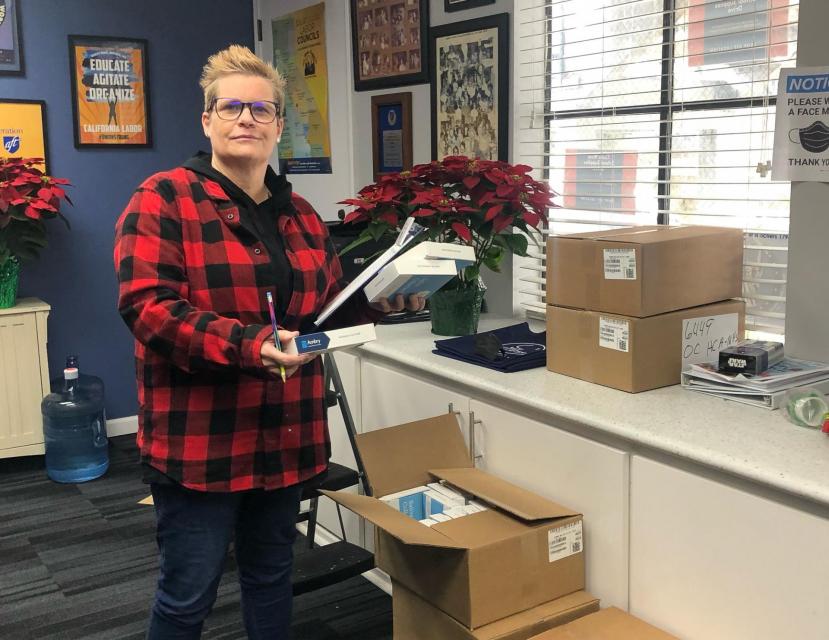

Jenny Hlebakos, vice president for the Petaluma Federation of Teachers, says the past few years have been brutal, and there has been a lot of burn out—sometimes leading to people leaving their jobs just days before the semester starts. This, in turn, she says, is hard on the mental health of students left without a regular teacher.

Hlebakos, a fourth grade teacher like Robledo, says the district is severely understaffed and the pay isn’t competitive. One of her friends substituted in Petaluma schools, where the parents and students loved her—but she couldn’t afford to stay there and went to Santa Rosa where the pay is significantly better.

In some ways, Hlebakos thinks the district is moving in the right direction, with a more diverse school board. As a person of color, that’s important to her, Hlebakos says.

But she adds that her school shares a counselor and an intern with another school, meaning two people to deal with a population of about 900 students.

“Something I’d love is the school district to find a way to have more staff to support the students who are going through so much,” she said.

— By Emily Wilson, CFT Reporter