Reviews by Bill Morgan

It used to be hard to find quality non-fiction, especially history, for kids. It was dumbed-down, or poorly formatted, or biased, or written in dry adultese, or some combination of these. Thankfully, that has changed.

A new generation of high-interest, attractively packaged kids’ books dealing with social justice issues and using leveled vocabulary are now available. This is a group of some of the best recent ones that I have used in my years teaching social studies for social justice.

For All/Para Todos

By Alejandra Domenzain

Illustrated by Katherine Loh

Hard Ball Press,

2021, 53pp

Ages 5-8

There are children’s books that take complicated concepts and tell them simply, like Octavio Chow’s The Invisible Hunters. There are books about strong, determined girls — Wilhelm Steig’s Brave Irene comes to mind. Books like Friends From the Other Side, and Click Clack Moo! speak to the immigrant experience, and to the power of writing, respectively.

It is remarkable, though, to find a children’s book that does all of these things, and does them all so well. Para Todos, a new book by Los Angeles labor organizer Alejandra Domenzain, is such a book. The protagonist is a girl named Flor, who comes to the mythical (or not so mythical) land of “Para Todos” with her father when they can no longer survive in their native country.

They arrive with a lot of hopes which are soon dashed as her dad is forced into back-breaking, low wage work, and Flor is ridiculed by classmates because she is different. A teacher suggests that she write about her life, and gives her a green pen. Flor never looks back. She writes about her own experience at first, and soon becomes a spokesperson for the immigrant experience in general, campaigning for better schools and better jobs.

Oh yes, the book is written in rhyming couplets, which is the sort of thing that normally bothers me. In this case, however, the rhymes have a relaxing kind of ring to them, as Flor faces one challenge after another.

OK. It’s all here. Strong Female. Social Justice. Metaphor for the Immigrant Experience. And Writing. I used tell my students that every time they put pencil (or green pen) to paper, they changed the world. So be it. Here’s to more Flors and more excellent books like For All/Para Todos.

Fred Korematsu Speaks Up

By Laura Atkins and Stan Yogi

Illustrated by Yutake Houlette

Heyday

Press, 2017, 103 pp

Ages 8-14

This book succeeds in several ways. First of all, it is informative. A simple, rather flat-footed narrative tells the story of Fred Korematsu, a man who successfully challenged his internment during the terrible days in the early forties when America turned on its own people and threw them into concentration camps. Their crime? Being Japanese.

Second, the book is crammed with original documents: primary source stuff like signs, photos, letters personal and official; newspaper articles, paintings and drawings by interned inmates; even the text of laws and acts of Congress; poetry, short bios and other relevant background material. And the illustrations are first-rate simple, but deeply expressive of the man’s and his community’s ordeal. So this book is more than a simple book, it’s a jackdaw, a collection which presents evidence of all kinds in a variety of genres and also pays students (fifth grade and above) the ultimate compliment — to decide for themselves.

“Have you ever disagreed with your family and friends about something important to you?” they are asked; “Why does discrimination happen?”; “What happens if you fail at something? Would you risk it to try again?”

There is a hard truth here, and the authors do not candy coat it: To challenge the government, as Korematsu did, and to win, as he also did, is a long and lonely road. Virtually everyone left him; his girlfriend, his family, his interned peers, and of course, his own country, America. All turned their backs to him.

We realize that one of Korematsu’s issues all through his life was that was too American — he preferred English to Japanese, had surgery done on his face to look whiter, loved swing music, dated white women and — believe it or not — actually thought the Bill of Rights meant something.

Imagine that!

The book also succeeds on a third level: This is the way to teach history. The narrative, sure. The illustrations, sure. Most kids’ books stop there. This one does not. You get the basic facts, but you also get a real taste of the age.

Teachers will have a field day discussing this stuff. How could such a patently unjust thing happen? Who enforced it? What came before it? What, after? What was it like to live in California then? Who resisted? Who helped Fred, and who didn’t? We are all acquainted with the textbook-based lecture, the superficial way of teaching history. This book invites projects, study in depth, and, best, a more direct involvement with the past and future. Repeat: This is the way to teach history.

Without our Fred Korematsus, legalized evil (in this case Executive Order 9066) goes unchallenged. And, to paraphrase Utah Phillips, “Our kids need to hear this stuff.”

Joelito’s Big Decision/La Gran Decision de Joelito

By Ann Berlak

Illustrated by Daniel Camacho

Spanish translation by José Antonio Galloso

Hardball

Press, 2015, 36pp

Ages 6-12

How do you write about social justice and keep kids involved? Too often, authors who can present an issue can’t write a good story, and even more often, the obverse is true; many stories either don’t touch upon or ignore social justice issues entirely. As teachers, we understand that kids learn best when they find themselves in the story, when the book deals with issues that touch them, too.

Such a book is Ann Berlak’s Joelito’s Big Decision, published by Hardball Press. The “big decision” referred to is whether or not to cross a picket line. It seems that Joelito’s family celebrates each week by eating at MacMann’s, a giant hamburger conglomerate. But now his best friend, Brandon, and Brandon’s parents, who work at MacMann’s, are picketing the place, demanding higher wages. To go in and cross the picket line or stay out and join it?

That would be quite enough, given Daniel Camacho’s rich and eloquent chalk illustrations that bring the whole thing to life. But that is not all the book is about. Along the way, Berlak touches upon the problems that poverty exacerbates: having to move because one’s house is sold; economic inequality (Mr. MacMann makes $9 million a year) and the reason for it (“MacMann has more money than he needs because he pays us so little!”).

Joelto and his sister Alma are latchkey kids — why? (Because both their parents have to work all day and some of the night?) Ms. Berlak even manages some labor history, as Joelito’s mother recalls how things changed in the fields when farmworkers stood up and demonstrated. And, she adds, Joelito’s grandmother like my own mother, would turn over in her grave if he crosses that picket line.

You gotta serve somebody. The choices we make either tend to serve the people who do the work or the MacManns who exploit them. How profound then; Joelito’s decision is our decision, too. We will run into the same choice over and over again in our own lives. How will you decide? Which side are you on?

Teachers of primary grades who are interested in social justice can do a lot with this book, because it opens so many avenues to explore. Perhaps Berlak and Camacho will make more such books. Here’s hopin’.

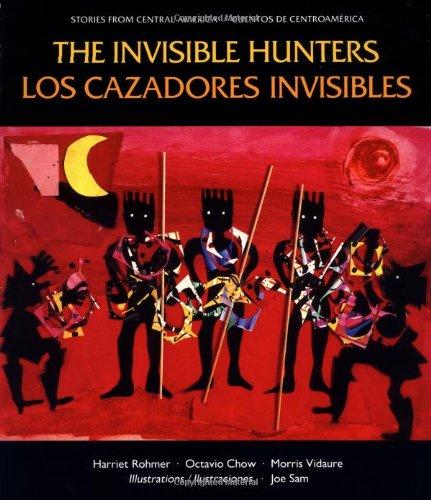

The Invisible Hunters

A Legend From the Miskito Indians from Nicaragua

By Octavio Chow and Morris Virdaure, with Harriet Rohmer

(Bilingual Spanish)

Illustrated by Joe Sam

Children’s Book Press (Lee and Low Books), 1987, 32pp

Grades K-4

One of the problems of teaching K-12 social studies issues is their complexity. Again, the familiar problem: How, do we talk to students about global warming, or immigration, or the labor movement itself without dumbing them way down on the one hand or making them too abstract on the other?

More or less inevitably, we resort to metaphors.

Metaphor: a figure of speech that directly refers to one thing by mentioning another.

A well-placed metaphor can summarize and reproduce the social relationships in a given situation. Example: Leo Lionni’s book Swimmy. Nominally, it’s a cute little fable about a group of small fish victimized by larger fishes. By uniting themselves into a composite big fish, they scare the attackers away. Suddenly the story is about organizing and working together — the very definition of unionism in simple and readily accessible terms. OK, good.

Now, how would you present economic relations and the shift from a subsistence to a market economy? This is where The Invisible Hunters comes in.

The Hunters are three brothers, and their work is to hunt for wild pigs — wari — to share with their tribe. There are plenty of wari for everyone because the Hunters are blessed by the Spirit of the Forest (the Dar) with invisibility, and because they only kill enough wari to feed their tribe.

Enter the Traders. (Columbus? Capitalism Itself?) These Traders seduce the hunters with the promise of riches and soon the link between the Hunters and their community is broken by greed. The result? Loss of the Dar, wari overkill, and rotten wari meat for their tribe. (The best wari meat is, of course, saved to sell to the Traders.)

Additionally, a well-turned metaphor allows us, as teachers, to address a whole variety of implied issues: Who are the Traders? Why do the Hunters lose the Dar? What happens when food becomes a commodity? Why did the brothers change? Is food a commodity nowadays? Why do so many people go hungry? Are the brothers right to try to get rich? Why or why not? And on and on.

The metaphor allows teachers to discuss and consider big abstract social issues in a meaningful way. Did I say “issue?” The Invisible Hunters opens the door to consider the whole shift from subsistence economies to capitalism and compares them. And that is a Big Deal.

About Bill Morgan

Bill Morgan is a retired San Francisco teacher, member of United Educators of San Francisco-Retired, AFT Local 61-R, and a member of the CFT Labor and Climate Justice Education Committee.

Morgan, and others on the committee, have authored and produced high-quality curriculum materials for educators. These are free to download; some are available in print at a minimal cost. Find the curricula here.