1950s: The Teachers Union that Came in From the Cold War

If the early 50s proved anything, it’s that the creation, preservation and extension of civil liberties of every generation have to be defended and won all over again by the next one. Heir to the Palmer Raids and Dies Committee witch hunts, McCarthyism scarred far more than teachers and their unions before it was through. For teachers in California, it defined the very atmosphere of the times, attempting and often succeeding in making any action out of the ordinary seem opposed to ‘freedom’, ‘democracy’ and ‘the American way of Life’.

The issue was not merely philosophical. Many federal and state laws were passed making new or continued employment contingent upon the signing of loyalty oaths; others made current or past membership in the Communist Party sufficient cause for dismissal. Congressional committees were set up to implement the new laws. The most famous, of course, was the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), and the person most directly identified with the anti-Communist crusade, Joe McCarthy. The witch hunts associated with these people and institutions bred their local counterparts, and they didn’t stop with persecuting Communists.

In New York more than 250 teachers were forced out of teaching from 1948 to 1953. 30 of these resulted from invoking the Fifth Amendment before one of several congressional committees; 31 after testifying; scores more had to quit under pressures direct and indirect. According to California Teacher (November-December 1954) the first teacher called to testify committed suicide on Christmas Eve, 1948. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, in a dissenting opinion when the Court upheld New York’s Feinberg law, stated that “‘What happens under this law is typical of what happens in a police state. Teachers are under constant surveillance; their pasts are combed for signs of disloyalty; their utterances are watched for clues to dangerous thoughts. A pall is cast over the classroom…”

On the other side of the country, a dozen Los Angeles teachers were fired under the Dilworth Act for taking the Fifth Amendment in front of the Velde Committee, which the editor of California Teacher called “a pocket edition of McCarthy in Los Angeles”. Dismissed from his longtime teaching post at San Diego State, former AFT Vice President from California Harry Steinmetz noted that for every teacher summoned before such bodies a thousand are

silenced. In the northern portion of the state, in an all-too rare management show of understanding for teachers’ predicament, it was the view of San Francisco Superintendent of Public Schools Herbert Clish that teachers “…are afraid to discuss controversial issues in the classrooms. They are afraid of community pressures.” A generation of children were denied teachers able to openly discuss and stand up for their ideas.

The CSFT’s defense of academic freedom and opposition to loyalty oaths stood out in those years from other education organizations with their meek, get-along attitudes. Two issues put the CSFT on the California education map in these years: defense of basic constitutional rights for everyone, including teachers; and the struggle between teachers and administrators to define authority over the classroom. Again and again the small union rose to defend teachers in conservative courts: the Elizabeth Baldwin tenure case (fired for being over 40); the case of Stan Jacobs’ dismissal for cause, and others too numerous to list. Two cases out of the many fought by the union in those difficult years will suffice to demonstrate these concepts.

Ed McGrath taught at Sacramento High School. After he questioned his principal’s authority to assign him to work as a “policeman” at school sports events in the evenings and on weekends, he was removed as chair of the social studies department and transferred to teaching English. He was also given a heavier teaching load than any other teacher in the district. McGrath filed suit the District Superintendent. His case was supported by Sacramento Local 31, the CSFT, the AFT, and various labor bodies. The CTA took no position until the day McGrath and his union attorney were in court pleading his case. A CTA attorney showed up, sat down with the Superintendent and his lawyers, and requested permission to appear as an amicus curiae, or friend of the court. The state president of the CTA later attempted to portray the CTA lawyer’s appearance as “neutral”.

McGrath lost the case in Superior Court and appealed. In Fall 1954 the case was heard in Appeals Court. McGrath lost again. But the significance of the McGrath case extended decision. Widely publicized in California Teacher and AFT local publications around the state, McGrath’s situation confirmed the suspicions of many teachers that their “professionalism” stood in inverse proportion to the number of “professional” duties heaped on their shoulders outside the classroom. His case reinforced their growing sense that this situation need not be eternal.

In 1950 the Levering Act became law in California, mandating a loyalty oath for employees of the state of California. The only California state senator voting against the bill was George Miller of Contra Costa County, a friend of the president of the Contra Costa County Federation of Teachers, Local 866, Ben Rust.

Shortly after passage of the Levering Act, Frank Rowe was hired to teach art at San Francisco State College. On principle, he refused to sign the Levering Oath. Eason Monroe, a colleague of Rowe’s and a tenured professor, told reporters, “The oath attacks the thing it purports to defend.” Monroe, like Rowe, was a CSFT member. Both were dismissed for refusal to sign. Monroe became the executive director of the ACLU in California, spending a fair amount of time in his new job fighting the law that had gotten him fired. The CSFT voted to extend a free year’s dues extension to Monroe in recognition of his services to teachers’ cause.

It wasn’t until 1967 that the Levering Act was declared unconstitutional by the California Supreme Court. Rowe’s case, along with others’ from San Francisco State, meanwhile dragged on for years, handled by the ACLU and later on by attorneys of United Professors of California, the state-wide affiliate of the CSFT in the colleges. He was finally given a class assignment in Fall, 1977, at San Francisco State. Since he had in the meantime become a full-time instructor at Laney College in Oakland (and member of Peralta Federation of Teachers, Local 1603) he taught the course chiefly for the symbolism of it.

The CSFT published a pamphlet in 1950 that declared, “The Levering Oath is in contradiction to the Federal Constitution since it imposes on public workers a political test for employment, deprives them of equal protection under the law as guaranteed in the 14th Amendment, and exposes them through its ambiguity to self-incrimination and perjury.” In contrast, the CTA supported the Dilworth law used to fire the Los Angeles teachers. Responding to a question from a member at a CTA legislative meeting in February of 1953, CTA leader Harry Fosdick weakly remarked, “The CTA has gone along with a lot of bills in the past…I think we will have to take a stand pretty soon on these ‘loyalty’ bills.” (The NEA invited speakers from the American Legion, one of the most outspoken advocates of loyalty oaths, every year to its convention from the Legion’s founding through 1959.)

Nowhere were the divergences in philosophy and willingness to act of the two organizations more clear than in the CSFT 1953 legislative program, its first attempt at sponsorship of a comprehensive package of bills. In addition to Dilworth, there were several more issues on which the teachers union and the CTA found themselves on opposite sides. The union created several bills carried by George Miller and a few other sympathetic legislators on pay raises, duty-free lunch periods, overtime duties unrelated to teaching, and–collective bargaining for teachers. The CTA had a hand in killing each of these proposals. The CSFT took solace that they had learned some important practical lessons about how legislation is created, and congratulated themselves on the solid public relations they enjoyed with teachers from press coverage.

The union had also broadened its field of battle. The lunch duty and overtime duties bills were an effort to extend the struggle begun with the McGrath case over control of teachers’ job descriptions and time away from the classroom. The union introduced these bills at a time when McGrath’s case had yet to be resolved, testing the waters over the same issue in a different setting.

The bill calling for collective bargaining for teachers, the first ever attempted, scored important points with many teachers sympathetic to unions yet not ready to take the risky step of breaking with the CTA to join a teachers’ union. CSFT’s action made the statement to these teachers that, together with legal defense suits and legislation, here was yet another way that problems might be resolved.

CTA’s opposition to collective bargaining for teachers was based on the idea that professionals don’t need unions. And this was the crux of the difference. The CSFT held that teachers aren’t professional just because other people call them “professional”: they need the real power over their work lives that professionals possess. Dominated by administrators, the CTA had an obvious stake in opposing this notion, because their opposition allowed their most powerful members administrators to continue to rationalize their control over a “teachers association”. These points of difference were hammered home by Ben Rust, President of the CSFT over the bulk of the decade, from 1951 to 1958.

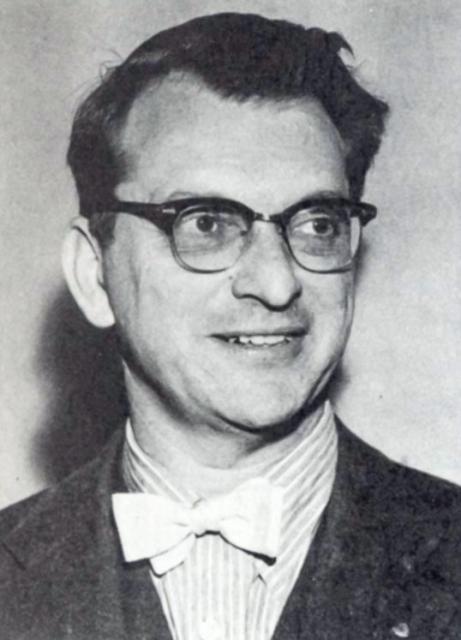

Rust’s brand of unionism sprang from his commitment to teaching and his skilled trades background. A prolific if homespun writer, Rust was author of numerous books, articles, studies and pamphlets on education, civil liberties, unionism, and other topics. He was absolutely dedicated to the mission of convincing teachers that the path to real professionalism led through the AFT. He possessed nearly endless tolerance for most human foibles, but drew the line when it came to the qualities needed in a teacher. In a diary entry he sternly (and ungrammatically) wrote, “Those who do not love learning, themselves, must not teach.”

Rust’s alternative to the CTA’s empty “professionalism” was the notion that teaching was a craft. On the way to becoming a Master Teacher the teacher should pass through an apprenticeship that forges the qualities of independence, scholarship and pedagogical sophistication. Rust’s vision proposed an organic link between the activities of teaching and the craft union tradition, and anticipated reform proposals of three decades later.

Relations with the rest of the labor movement were a constant source of concern for Rust. While outwardly expressing nothing but enthusiasm for the CSFT’s labor affiliation, he confessed frustration periodically in his personal diaries with the fluctuating level of support offered teachers by unions. Despite occasional setbacks, Rust’s tireless work shuttling back and forth between his membership and other labor groups was a key factor in nourishing the growth of the teachers’ union.

Rust was a liberal idealist. He presided over and encouraged the contention of all shades of political opinion within the union. He was committed to “The Spirit of the Bill of Rights” (the title of one of his publications), as well as to the letter. It was Rust at the 1953 national AFT convention who, fighting a rearguard action against resolutions calling for the firing of Communist teachers, introduced a resolution that stated: “While we oppose the employment of Communists in our schools we decry the dismissal of competent employees solely on the ground that they availed themselves of their legal and constitutional rights as guaranteed in the Bill of Rights.” The resolution passed by a wide margin.

Rust’s idealism tempered a direct, practical side of his character. Under his direction the CSFT hired its first full-time staffer, Henry Clarke, and put an attorney on retainer for legislative and legal duties. California Teacher moved from mimeo to print, regularized its publication and was distributed in increasing numbers. Rust raised the funds for this transformation from other unions.

Rust convinced the legislature and many teachers to accept the CSFT as the voice of classroom teachers over the CTA. But perhaps his most important accomplishment was to hold together the northern and southern halves of the organization when Local 1021, smarting after failing to elect their slate at the CSFT convention in 1952, withheld per capita dues payments to the CSFT for over two years. After repeated entreaties by Rust and others to Local 1021 president Walter Thomas, the Los Angeles local was declared in “bad standing”. Disgruntled northern CSFT leaders; sympathetic to the outcast local 430 anyway, wanted to reaffiliate them and cut 1021 loose completely.

The worst polarization occurred in late 1954. Fred Clayson, editor of California Teacher, Published an unprecedented 24-Page, two-color edition, replete with long articles supporting the expelled leftwing teachers’ unions in Philadelphia, New York and Los Angeles. The Executive Council asked for and received Clayson’s resignation. Within a year Local 1021 had reaffiliated.

As the CSFT began to create a viable statewide presence through regular meetings and publications, proposals for legislation and slow but steady growth in membership, the differences between the teachers’ union and the education association became obvious to teachers who genuinely cared about education and its place within the broader society. CSFT Executive Secretary Henry Clarke – who was soon to become a national AFT staffer – pointed out in 1955 that “There has been real purpose behind the CTA legislative program this year. That purpose has been to establish the CTA as the most powerful, best disciplined company union’.” An increasing sharpness of tone toward CTA is discernable in the California Teacher as the decade progressed, based on the CSFT’s surer footing and continued conflicts with the association at the local level and in Sacramento.

From fewer than a thousand teachers in 1950 the CSFT membership had more than doubled by the mid-50s. The uneasy marriage of northern ‘ideological’ unionists and southern ‘bread and- butter’ types seemed to be working, and each side of the state organization continued to do what they did best in the latter part of the decade. In Los Angeles, thanks to efforts by AFT national staffer Kent Pillsbury, CSFT organizer Henry Clarke and especially local 1021 member Evelyn Carstens, the union picked up hundreds of members when it secured exclusive partnership with Kaiser for health benefits for District teachers, pushing Local 1021 over the 1,000 mark by 1959. In an indication of the growing rivalry between employee groups at the time, the local’s Eddie Irwin, elected a national vice president of the AFT in 1954, nearly came to blows with an Association representative at a School Board meeting over the question of payroll deductions of union dues. lrwin and Hank Zivetz, both gifted speakers, acted as if they represented all L.A. teachers, and convinced many that they did.

Meanwhile, northern locals demonstrated for civil liberties and pushed through resolutions condemning the latest outrages by HUAC at CSFT conventions, and seemed to thrive on that diet: San Francisco Local 61, for example, steadily gained adherents, with over 600 members by 1958; the local exceeded membership targets each year in the decade. Increasing legislative successes came in the late fifties. In 1957–the year that racially segregated AFT locals in the Southern United States were expelled from the national organization – the CSFT worked closely with Los Angeles teacher and AFT member Wilson Riles to write and sponsor SB 2556. Introduced by state senator Richard Richards, the bill established the Commission on Discrimination in Teacher Hiring, the first fair employment practices legislation adopted by the state. It prohibited discrimination in employment of certificated employees. CSFT Executive Secretary Don Henry was named to the Commission by the state superintendent of schools.

In 1959 Ben Rust chose not to run for re-election. Despite the union’s successes, Rust felt the strain of attempting to build and hold together an often fractious statewide organization while teaching full-time. The CSFT had had to replace Hank Clarke when the national AFT hired him as its Western Regional staffer. The new Executive Secretary, Don Henry, did not mix well with Rust, and after a few years Rust decided that he would devote himself to teaching. During his tenure the organization nearly tripled in size and stabilized for the first time in its history. Rust’s visionary legacy to the California Federation of Teachers - unionism in defense of teaching as a craft – is honored by the annual bestowal at CFT conventions of the Ben Rust Award.

The new president, Lou Eilerman of Long Beach, led the CSFT into the next decade. An art teacher, Eilerman, like Rust, saw teaching in terms of the craft union tradition. Not as politically sophisticated as Rust, he had to learn parliamentary procedure when he became president in order to run the meetings. Nevertheless, he oversaw the greatest successes yet for the CSFT in the legislative arena in 1959. Several CSFT bills were written into law, including one mandating back pay to teachers reinstated after wrongful dismissal.

Symptomatic of the changing tenor of the times, the case of three teachers from Eilerman’s Long Beach local, beginning in late 1958, helped stimulate passage of CSFT legislation for probationary teacher protection within a few years. The contracts of these probationary teachers were not renewed; during the court trial sensational evidence, splashed across the front pages of Long Beach newspapers, came to light about FBI spying on one of the teachers for his political activities. While Cold War overtones colored the case, the outcome in 1951 (protective legislation) was different than it might have been a decade earlier.

Eilerman brought the CSFT out of Ben Rust’s pockets and installed it in an office with a phone, mimeograph machine and filing cabinets. It was also during Eilerman’s presidency that the first college locals of the CSFT were chartered, including several community colleges and state colleges.

One more small event, but a milestone of sorts, must be noted. In late 1958 the first California AFT local won collective bargaining rights. Representing teachers in film and TV studios in Los Angeles, the private sector victory of Local 1323 foreshadowed the accomplishment of the teachers’ union nearly two decades later, when a collective bargaining bill for public school employees was finally signed into law. But before that story can be told another must be recounted: the 60s.