1930s: A “Debating Society” Struggles to Survive

If the previous ten years had been traumatic for teachers and their union, the early 30s proved nearly unbearable. Added to all their other problems was the minor difficulty of national economic collapse. More than a quarter of the nation’s population became unemployed in the years following the stock market crash of 1929. After Franklin D. Roosevelt’s election in 1932, on a Democratic Party platform lifted plank by plank from the Socialist Party’s (social security, unemployment insurance, labor law and banking reform, minimum wage, etc.) working people began to feel some hope for their future. But before the New Deal programs started to make a difference, prospects remained bleak for teachers. Speaking of the effects of the Depression in his 1935 article in American Teacher, “The Teacher and the Public”, John Dewey explained,

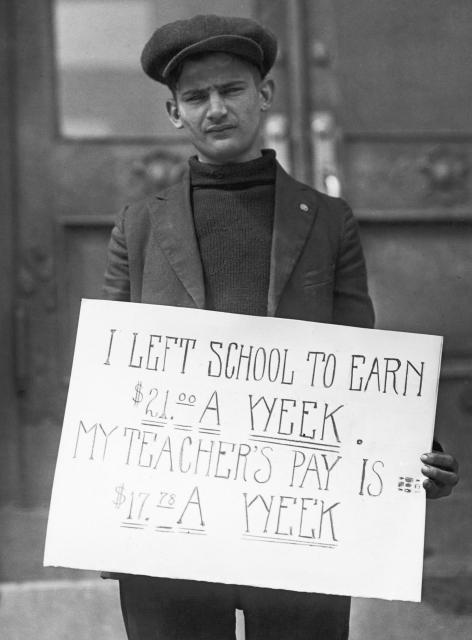

Salary or wage cuts are almost universal. Multitudes of schools have been closed. Classes have been enlarged, reducing the capacity of teachers to do their work. Kindergartens and classes for the handicapped have been lopped off. Studies that are indispensable for the production of the skill and intelligence that society needs have been eliminated. The number of the unemployed has been increased in consequence, and the mass consuming power necessary for recovery has been contracted.

The lot of the teacher was worse than it had been when the AFT was formed twenty years before. But teachers were not alone. The AFL’s strategy of cooperation with the employers reaped bitter fruit; its membership plunged to less than 10% of the workforce. Observers wondered whether it might not disappear altogether. The craft union orientation of the AFL was not well-suited to organizing the new mass production industries; some of its leaders’ elitist attitude toward unskilled workers ensured that these mostly immigrant and second-generation workers wouldn’t become union members. AFL leaders also refused the entreaties of the more progressive unions within its ranks to try to ameliorate the lot of the unemployed.

Dissatisfaction with the lack of militancy of the AFL leadership and disagreement with its strategies led several unions, pushed by John L. Lewis’ United Mine Workers, to break away from craft unionism in 1935 and found the Committee for Industrial Organization, later Congress of Industrial Organizations – the CIO. Committed to organizing the unorganized, the unskilled alongside the skilled, the unemployed as well as working people, and to a model of militant, bottom-up action, the CIO unions helped support a wave of militancy that created the modern American labor movement. The passage of the National Labor Relations Act, or Wagner Act (1935), giving workers the legal right to organize and form unions, opened the floodgates, pushing the AFL into organizing, too.

The AFT debated leaving the relatively conservative AFL for the militant CIO, with some locals – such as New York’s Local 5 and Los Angeles’ new Local 430 – establishing independent contacts and joint activities with local CIO unions. The national AFT, however, after protracted debates in conventions and in the pages of American Teacher, decided that its best course of action was to work for unity of the two labor federations from within the AFL.

The discussions within the AFT must be understood in context. The Depression led many Americans to conclude that the capitalist system had failed. Before revelations had reached these shores about life under Stalin, the Soviet Union seemed to offer a rational alternative. The Communist Party attracted intellectuals and workers by the thousands, and like the IWW before it, influenced the thinking and actions of many more. From the mid 30s to the late 40s ardent defenders of civil liberties, militant unionists and other activists in progressive movements joined or worked with the Communists (and Socialists and Trotskyists) because they spoke out and acted against injustice and in favor of a better world for all.

In the AFT political divisions between liberal, bread-and-butter unionists in Chicago and the Midwest and their more leftwing, ideologically-inclined counterparts in New York and Philadelphia nearly tore apart the union. The battle over CIO affiliation was but one consequence of this political split within the AFT.

Despite its internal conflicts the national teachers’ union made slow but steady progress throughout the 30s. Tenure, salary and the fight against cutbacks were again leading issues for the AFT, and its stands on these matters helped raise its membership from 7,000 to 32,000 (mostly in New York and Chicago). The AFT, in fact, despite its modest size, found itself at the center of the struggle over education in many localities, since boards of education, with the hand of chambers of commerce behind them, sought to cut programs’ and labor councils were needed to counterbalance the struggle. The small teachers’ unions were well-placed to bring the rest of labor into the ballgame.

As for tenure, an editorial in the November/December 1936 American Teacher declared it to be “the chief problem before us at the present time,” stating that “It precedes even salaries and academic freedom since tenure is a prerequisite for both.” At the end of 1936, 27 states, accounting for over 50% of all teachers nationally, still had yearly individual contracts for teachers or no contracts at all. The AFT Passed resolutions at its conventions, got labor

to do the same, built educational coalitions and pressured local and state legislatures to pass tenure laws.” It also drafted model tenure language and offered its assistance to locals and state groups of teachers.

As in the 20s, another central concern was the defense of academic freedom. The legal defense case of Morris U. Schappes in New York helped spark membership growth in Local 5 among college professors, even while that local was in turmoil over internal politics. The president of the national AFT during the mid to late 30s, Jerome Davis, was fired from his professor’s post at Yale University after teaching there for 12 years for his union activities and left-wing political sympathies. His defense campaign brought protests from the NEA, AAUP, and Progressive Education Association against Yale, which finally responded by paying him an extra year’s salary. (It didn’t rehire him, however.) The 1936 AFT convention featured a debate and resolution condemning loyalty oaths as a condition of employment; so much attention was devoted to the issue that it became the theme of the meeting.

In cities where cutbacks, large pay cuts, payment in scrip and delayed checks were common, teachers flocked to the union. The New York local grew from 1500 to 4200 in just over six months despite a split that lost several hundred members. A separate local of Works Progress Administration (WPA) adult education teachers, with a membership of 2500, was organized rapidly at about the same time. WPA teachers were usually public school teachers on welfare.

These successes led the newly hatched House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), led by Martin Dies, to turn its baleful eye on teachers union activities in 1938. This variation of the recurrent Red Scare, less effective than either the earlier Palmer or later McCarthy versions, nevertheless kept the AFT and other progressive organizations busy defending their basic constitutional rights. The difference between this and other Red Scares was the steadily growing strength of the labor movement, backed by the ability of the liberal New Deal administration to defend its allies.

The CSFT

In marked contrast to the AFT’s growth in the Midwest and East Coast was stagnation in California. A measure of the poor shape of the CSFT comes to us via a report on the semi-annual meeting of the organization in 1932. Recounting the visit of the AFT national Executive Secretary, Florence Hanson, to the state federation meeting, the report tells us that

The widespread demand for economy, the weight of the depression, coupled by an insidious public press attack had discouraged all but the leaders of the few locals that have weathered the storm; but with the coming of Mrs. Hanson to San Francisco a new spirit has been engendered; hope has revived; a re-awakened interest sprang to life, and many cities called for the charmed voice, the magic touch of our National Executive Secretary.

Apparently this “new spirit” didn’t last long, for in CSFT secretary Anne Dart’s American Teacher article on “Tenure in California” in March-April 1936 we find a similar celebration of ‘renewal’:

We are very hopeful of our situation in California. Some of us have clamored rather loudly for the State Federation of Teachers to get into action again. Our state convention was a success, and we now have in California eight locals. We have banded together in the tenure fight the bravest and most knowing school men and women in California, all of whom enjoy the “storm and stress” of fighting things to the finish. We know that academic freedom, organization, and tenure are all parts of the same struggle toward a better life for all workers.

The deaths and births of the CSFT followed upon one another in increasingly rapid succession; by the September/October American Teacher the journal was able to report once more that “The California State Federation of Teachers has been reborn and is now living an active career.”We may infer from these repeated protestations of health that the patient was in serious trouble. During this period there were no regular statewide publications; no records come down to us of CSFT presidents between 1933 and1939; and by 1940 the national organization was warning the CSFT that it was in danger of losing its charter for lack of enough active locals.

All was not quiet, however. The national struggle conducted by the AFT for tenure included skirmishes in California. In each legislative session, anti-labor forces introduced bills to roll back the 1921 tenure law, already weakened in 1927 (with California Teachers Association approval) to exclude teachers in districts with less than 850 average daily attendance. In 1933 a provision was added to the law allowing teachers to be dismissed for “criminal syndicalism”, which, two years before the passage of the Wagner Act, essentially meant union activities. The weakened state of the CSFT, and the willingness of the CTA to wage battles against union-sponsored amendments to strengthen tenure (1936), resulted in short careers for many teachers.

One cause that did manage to ignite statewide support and galvanize a CSFT struggle was the case of Eureka teacher Victor Jewett. A member of the CTA (and later, AFT Local 349), he had received excellent evaluations throughout his five-year career as a social studies teacher. Then he committed the crime of “unprofessional conduct.” The evidence of Jewett’s unfitness to teach were: his expression, both within and outside of school, of his opposition to war; his condemnation of William Randolph Hearst’s “Buy American” campaign; and use of The Nation, New Republic and Living Age magazines as references in his class. But by far the blackest mark against him was his support of a local lumber workers strike. In a caustic article printed in the AFT’s national press, Jewett ridiculed the hypocritical type of “professionalism” espoused by his enemies, and delineated the reasons why true professionalism lies in teacher organization.

After he was fired by the Board of Education, he filed suit, and the Superior Court upheld his dismissal. His own organization, the CTA, disavowed him, and Jewett reported that “calumny against me has been spread by officials of that association.” The CSFT organized a defense committee, raised money, and hired an attorney for him. AFL unions, along with AFT locals from around the country, provided funds to appeal the Superior Court decision. The Education Association and its affiliates were finally pressured into lending assistance to Jewett’s cause. Ultimately, however, Jewett lost his appeal.

The CSFT was generally less than the sum of its parts in these years. California had its regional counter parts to the academic luminaries associated with the AFT back east, notably Professors Ernest Hilgard of Stanford and J. Robert Oppenheimer of UC Berkeley. Hilgard, chair of the Psychology Department at Stanford and author of an important work on hypnosis, served as president of his local in the late 30s. The physicist Oppenheimer, later to head the top secret Manhattan Project that developed the nuclear bomb during World War II, was at least an activist and possibly local president as well. Despite such distinguished assistance, no individual took responsibility for steering the CSFT through its rough times.

A few locals sustained the thin statewide presence of the union. Local 31 published a regular newsletter, The Teachers’ Voice, and its pamphlet “Organized Labor, Staunch Friend of the Schools” was reprinted by the American Teacher. It generally functioned as the lobbying arm of the state federation throughout the 20s and 30s. The San Francisco Federation of Teachers Local 6l maintained a lobbyist in Sacramento to augment the efforts of Local 31 in the early 30s, until declining membership forced them to discontinue the practice. Local 61 also broadcast a weekly radio program, and led the efforts to defend tenure in San Francisco. The union played a vigorous role in protecting the raises teachers won in 1930 against continuous efforts to cut salaries throughout the Depression.

Within its limited means, the CSFT worked to organize new locals. During the 30s fourteen locals were chartered, of which six survived into the next decade. One of the most significant occurrences for the CSFT was the founding in 1935 of a viable local in Los Angeles. The CSFT was determined to open Los Angeles, with the largest school system in the state, to teacher unionism. An earlier union, Local 77, had never managed to gain more than a few dozen adherents. Despite several trips south by CSFT’s second president, E.J. Dupuy, in the early 20s, enthusiasm for labor affiliation did not overtake the L.A. teachers. Local 77 succumbed to continuous attacks by the School Board, aided by redbaiting editorials in the notoriously anti-union Los Angeles Times.

Local 430 was chartered under different circumstances: with the support of a rising labor movement and amid increasing dissatisfaction among L.A. teachers with their several clubs and associations. It went on record opposing the dismissal of some teachers, and succeeded – with labor assistance – in reversing one dismissal. As a result of the celebrated Chaney case, in which two teachers fired for activism in the peace movement and the teachers’ union were rehired, the local also got the School Board to rescind an old Palmera prohibition against teachers joining unions. Nonetheless, Local 430 did not grow like a prairie fire. Teachers in Los Angeles chose AFI membership almost exclusively out of ideological commitment. While its membership rose to over 100 within a few years, making it the largest at the time in the CSFT, that wasn’t saying much, especially in a school district with over 11,000 teachers.

But the formation of the L.A. local did have its impact on the CSFT. Recognizing that the weaknesses of the state organization hurt the locals, Local 430 helped push the CSFT to meet regularly in the latter half of the 30s. Local 430 members became state officers and infused new blood into an all but defunct outfit. This is probably the meaning of at least the last of the reiterated statements of “new life” for the CSFT cited earlier. In return, in the late 30s the CSFT helped raise funds to support defense cases for L.A. teachers.

But the overall picture was not bright. Of the 42,000 teachers employed in California in 1939, 37,000 belonged to the CTA. In many districts CTA membership was a prerequisite for teaching, and it was expected that your first month’s salary be paid to the CTA as price for the privilege of becoming a member of the “profession.” None of these extenuating circumstances, however, was of much consolation to the members of the CSFT, which in the Depression decade had advanced only marginally from 300 members in 1930 to somewhat less than 500 in1939. Under these conditions the statewide teachers’ union was functionally, in the words of several participants of the time, little more than a debating society.